Venezuela is a South American nation located on the northern coast of the continent, bordered by Colombia, Brazil and Guyana. According to homosociety, it has an area of 912,050 square kilometers and a population of approximately 28 million people. The capital city is Caracas and the official language is Spanish though there are dozens of other indigenous languages also spoken in certain regions. Venezuela has a diversified economy with significant contributions from industries such as petroleum, agriculture, manufacturing and tourism. It also has some natural resources including oil, iron ore and gold as well as other minerals such as copper and bauxite. In recent years the country has seen a sharp decline in economic growth due to political instability however it still remains a popular tourist destination due to its vibrant culture and stunning landscapes.

When the Spaniards in 1498 arrived in the territory that would later become the Republic of Venezuela, there were a number of indigenous groups in the area from the Caribbean coast in the north to the Amazon jungle in the south. These were almost wiped out over the next few decades.

The capital Caracas was founded in 1567. Gradually a more centralized political structure emerged, while Venezuela became part of the trade route between Latin America and the European continent. On July 5, 1811, Venezuela was declared independent of the Spanish Empire, and the ensuing decades were marked by constant fighting and wars between various factions.

In the early 20th century, Venezuela was changed forever; they found oil. Already in the 1920s, the country was the world’s largest oil exporter. The oil wealth has continued to influence the country’s economy and political development to this day. In 1959, the country’s last dictator, Marcos Pérez Jiménez, fled the country, and representative democracy was formally introduced. See abbreviationfinder for geography, history, society, politics, and economy of Venezuela.

While the 1960s and 1970s were characterized by optimism for the future in parallel with major socio-economic differences, the political and social conflicts increased during the 1980s and 1990s. In 1998, Hugo Chávez won the presidential election, and Venezuela underwent a comprehensive political and social change process, often called the Bolivarian Revolution or the Bolivarian Process.

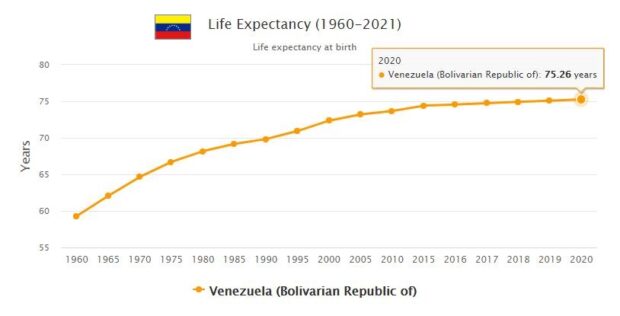

- COUNTRYAAH.COM: Provides latest population data about Venezuela. Lists by Year from 1950 to 2020. Also includes major cities by population.

Early history

The earliest finds of stone implements date from the savannah area of the state of Bolívar, around 5500 BCE, and represent a hunter-gatherer tradition. Along the coast, a somewhat later fishery and coastal anchor culture developed. From about 1000 BCE. won a horticulture based on bitter craze. Later, the maize came into being and formed the basis for agriculture, permanent settlement and craft specialization. The ceramic craftsmanship developed, as did stone work and weaving.

The goldsmith’s art, on the other hand, was not very widespread in this area; the metal objects found are originally from more western regions, today’s Colombia. This so-called Caribbean tradition came to dominate much of northern South America and the islands of the Caribbean.

At the time of the conquest, this form of culture encompassed a number of Caribbean- and Arawak- speaking people. Many of them were integrated into small states, chief judges and tribal alliances, including lache, chitarera and corbago in the highlands and jirajara, gayón and cuiba along the coast. These all spoke Caribbean, while the caquetio at the Venezuelan Gulf spoke arawak.

Near the Orinoco Delta were other Caribbean-speaking people such as teque, toromaina and caraca (which has given the name to the capital). All these peoples and nations disappeared shortly after the beginning of the colonial era. (See American Indigenous Languages.)

The colonial past

Kristoffer Columbus arrived on the coast of Venezuela in 1498, and the following year an expedition led by Alonso de Ojeda traveled inland. In the Maracaibo lake, the indigenous people lived in huts on piles, and Ojeda christened the country of Venezuela (‘Little Venice’).

The first Spanish city in South America was founded here in 1523 and was named Cumaná. German colonists asserted themselves for a while, but Spain gained control of the area in 1546. Caracas was founded in 1567. Sugar, tobacco, cocoa and hides were exported, but trade was controlled essentially by French, British and Dutch free trade people until Spain introduced monopoly. to trade in the early 18th century. This led to great dissatisfaction and uproar among the local Venezuelan trade stand in 1749.

The Spanish colonial bureaucracy did not have conflicting interests with the local landowners. These made extensive use of local and African slaves on large estates and plantations. For the first 200 years Venezuela was ruled from Santo Domingo, and in the 1700s from Bogotá until Venezuela became its own general capitol in 1777. The Creole bourgeoisie (Europeans born in Venezuela) became important initiators of the independence movement in Latin America.

Independence

In April 1810, the Creole took advantage of Spain’s weak position during the Napoleonic wars and deposed the Crown’s representatives in Caracas. In July 1811, Francisco de Miranda declared Venezuela independent. The war between the Creole and Loyalists continued for ten years until the Creole, led by Simón Bolívar, took full control in June 1821.

Bolívar’s ambitions were a large nation (Greater Colombia) that consisted of Veneuzuela, Colombia and Ecuador. Bolívar’s campaign for independence extended all the way to Peru and Bolivia, but before Bolívar saw his dream come true, in 1830 General José Antonio Páez proclaimed Venezuela an autonomous republic, becoming the country’s first president. Páez ruled in the interest of conservative landowners and dominated the country’s politics until 1848.

The period was characterized by an economic upswing, with the help of foreign banks, and a centralized state structure in which the army occupied an important position. The church lost its tax exemption and its monopoly on teaching. Slavery was still an important part of the landowner’s economy.

Conservative and Liberal

From the 1840s, an opposition movement emerged in the form of the Liberal Party demanding expanded voting rights, abolition of slavery and economic reform. General José Tadeo Monagas was elected President of the Conservative Party in 1848. However, he appointed Liberal Ministers and gradually moved to represent the Liberal Party.

Brothers José Tadeo and José Gregorio Monagas ruled the country with dictatorial power for ten years. New liberal laws were passed, but few were implemented. The economy stagnated, and the Monagas dynasty was deposed in 1858 by a joint action of the liberals and conservatives. After a bloody war and political chaos, Liberal General Juán Falcón succeeded in establishing a government in 1864-68. After a new period of civil war, Venezuela regained some stability again in 1870 under Liberal General Antonio Guzmán Blanco, who introduced liberal reforms. Despite great turmoil, he retained power until 1888.

Oil nation

The turn of the century marks a shift in Venezuela’s political history as well. In 1899, General Cipriano Castro took power by a coup and began a period of 36 years of military dictatorship and economic mismanagement. Conflicts with foreign companies led to naval blockade of Venezuela in 1902 and Dutch attacks on the navy in 1908. That same year, Juan Vicente Gómez took over as dictator, and in a short time he developed a complete monarchy. The army and police were significantly modernized, and violent methods were used to control the political opposition.

The discovery of oil deposits in Lake Maracaibo in 1911 ushered in a new era for the Venezuelan economy, which until then had been based on weak agricultural production and mining. Dutch and British interests, united in Royal Dutch/ Shell, began extensive oil exploration and exported crude oil from 1917. Later, the American Standard Oil also joined the recovery.

Gómez entrusted the entire business to the foreign companies and benefited well from the licenses. National planning was poor. Good wages in the oil business attracted workers, and agriculture suffered for this. Strikes were effectively knocked down by the army. Already in 1928, Venezuela was the world’s second largest oil exporter after the United States. Oil exports saved the country from economic collapse during the economic crisis of the 1930s, but the wealth fell to the elite of the country and was invested in prestige projects and the development of Caracas into a modern metropolis.

Gómez exercised total power until his death in 1935. His successor Eleazar López Contreras introduced certain reforms such as trade union rights and public education.

Transition to democratic elections

By the end of World War II, oil exports had picked up, and a newly formed political party, Acción Democrática (AD), assumed power with broad support in the population. The leader of the party, Rómulo Betancourt, and his civil-military junta devised a new constitution based on social-democratic principles. Drastic reforms were implemented, but in 1948 the army put a stop to a military coup.

The next decade was characterized by corruption, brutal oppression of the opposition and an intimate relationship between North American oil companies and the power elite. Nearly 70 percent of all investments in Venezuela were North American, and the oil companies acquired more than 90 percent of their revenues. In 1958, General Marcos Pérez Jiménez was overthrown in a public uprising with support from parts of the Navy and the Air Force. The beginning of a democratization process was underway, and Romulo Betancourt was elected president of AD in December 1958.

Puntofijo Pact

A few months before the 1958 election, AD and the Christian Socialist COPEI had signed a political pact called the Puntofijo Pact (Pacto de Punto Fijo). The agreement ensured that the two parties would cooperate politically while switching to government power and excluding other political movements (especially the communists) from gaining political power. This led to a political hegemony that would last for 40 years.

Until the beginning of the 1980s, this led to a relatively stable and nationalist development with good help from oil revenues, at the same time as political dissent was strongly suppressed and the socio-economic inequalities were large. In the 1960s, several rural and urban guerrilla groups were active, but these were severely beaten down by the authorities and eventually eradicated.

The crisis begins

While much of Latin America suffered military dictatorship in the 1970s, the Social Democratic Party dominated AD under the leadership of Carlos Andrés Pérez of Venezuela. For the OPEC country, the oil crisis in 1973 meant even greater revenue, and in 1975, the Pérez government nationalized the ironworks and the year after the oil business. The state oil company Petróleos de Venezuela SA (PDVSA) has since been the cornerstone of a network of state companies.

The 1979 oil crisis added Venezuela to a series of debt-ridden countries in Latin America. The governments of Luis Herrera Campins of COPEI (1979–84) and Jaime Lusinchi of AD (1984–89) were characterized by structural adjustment reforms following guidelines from the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which led to a sharp reduction in public services, a sharp rise in prices, increased unemployment and poverty.

El Caracazo

In the pre-election campaign ahead of the 1989 presidential election, Pérez vowed to step up further IMF-dictated reforms. Instead, he had made a secret agreement with the Fund for Further Reform, which came into force on February 28, 1989. This led to a spontaneous uprising called ” El Caracazo “, triggered by the rise in the price of public transport overnight as a result of the Gasoline prices were sharply raised.

The riot started among a group of bus passengers in the satellite city of Guarenas outside Caracas early on the morning of February 29, and quickly spread to Caracas and other major cities. Pérez’s government and Caracas mayor Antonio Ledezma sent police and the army to stop the uprising in the poor neighborhoods. The military fired unarmed sharply, killing somewhere between 300 and 3,000 people – the exact figure has never been known.

Political chaos in the 1990s

From an historical perspective, the El Caracazo uprising is considered a turning point in Venezuela’s history. For the poor, it was a shock to be subjected to violence of such proportions, which led to the political elites and the political system being considered illegitimate. Many soldiers, who themselves came from a poor background, were upset about being sent out to kill “their own.” In addition, Pérez’s government was also accused of widespread corruption and participation in criminal activities. In 1992, the government was subjected to a coup attempt by a wing of the military, led by Hugo Chávez. The coup was unsuccessful, but the attempt, and Hugo Chávez himself, gained great popularity.

Pérez was on the defensive and fought hard to maintain his political integrity. But a new coup attempt in November 1992 led to stronger demands that Pérez had to step down and be brought to justice for corruption. Pérez was ousted in 1993 and replaced by Senator Ramón José Velásquez, who served as interim president until the election later that year.

The election was won by Rafael Caldera (president 1969–74), who in 1991 broke with COPEI and founded the party Convergencia (C). The Caldera government, which took over 1994, was hit by the same economic crisis that had affected the previous government. In a few months, the currency unit Bolívar underwent a devaluation of 80 percent as a result of one of the country’s largest banks, Banco Latino, went bankrupt. Oil revenues were drastically reduced and Venezuela experienced the worst economic crisis in the country’s modern history. In the streets there were continuous demonstrations.

In June 1994, the government introduced price controls to curb riots, state control of the banking system, expanded police authority to make arrests and execute prisons, and certain restrictions on freedom of movement domestically. These restrictions were lifted in 1995.

Hugo Chávez and the 1998 elections

After the coup attempt in 1992, Hugo Chávez was jailed. In 1994, he was pardoned by Rafael Caldera, who would earn Chavez’s popular popularity. Chávez created the political party Movement for the Fifth Republic (Movimiento Quinta Republica, MVR), and in 1998 he won the presidential election with 56 percent of the vote, ending AD and COPEI’s 40-year political hegemony. Chávez’s electoral victory ushered in a whole new political era in Venezuela.