Iceland is a country located in Northern Europe, bordered by the Atlantic Ocean and Greenland. According to homosociety, it has a population of around 364,000 people and an area of 103,000 square kilometers. The capital city is Reykjavik while other major cities include Akureyri and Hafnarfjörður. The official language is Icelandic but English is also widely spoken. The currency used in Iceland is the Icelandic Króna (ISK) which is pegged to the Euro at a rate of 1 ISK: 0.0076 EUR. Iceland has a rich culture with influences from both Norse and Celtic cultures, from traditional music such as Icelandic folk music to unique art forms like Þorpið art. It also boasts stunning natural landscapes such as Snæfellsjökull National Park and Vatnajökull National Park which are home to an abundance of wildlife species.

Iceland’s history begins in the 8th century, when the island, located in the northern Atlantic Ocean, was populated, mainly from Norway and the British Isles. Iceland was then a free state until the 1200s, when the country was subject to the Norwegian king. After the Reformation in 1536, Iceland formally became part of Denmark. In 1918 Iceland became an independent state, but in personnel union with Denmark. Following a referendum in 1944, Iceland was declared an independent republic.

Before 1150

Iceland settles

Irish monks must have been the first to settle in Iceland, but they disappeared when the Norwegians arrived. See abbreviationfinder for geography, history, society, politics, and economy of Iceland. The Norwegian Viking Naddodd and the Swede Gardar Svåvarsson are said to have come to the island around 860, and it was for a time called Garðarsholmr. In 868, Floke Vilgerdsson probably went to Iceland from Rogaland: he landed in Vatnsfjörður, but the land fail failed. Because of all the drift ice on the northern part of the island, he called the country Iceland.

The first permanent settlement was probably initiated by Ingolv Arnesson from Fjaler, who took land there in 874. About the landmark (ca. 870–930) tells the unique Landnámabók, which mentions 430 landmen. Most of them were Norwegian men who, according to Landnámabók, went to Iceland to escape Harald Hårfagre’s hard rule. Whether that alone was the reason can be questionable. Some settlers also came from the North Sea Islands, and there was a Celtic element. How strong it may have been, historians disagree.

The chiefs brought with them relatives and friends, a large number of slaves and cattle. Around 930, the population may have reached 9000. The first settlers took up large areas, and by about 900 the entire island was occupied. Later immigrants had to get land from the chiefs. The climate was milder than today, and grain was grown, but livestock farming, fishing, whaling and sealing were the most important industrial routes.

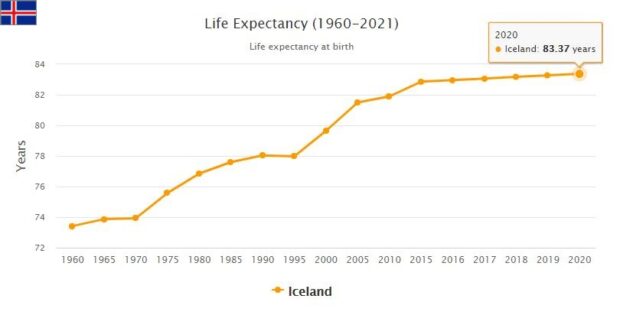

- COUNTRYAAH.COM: Provides latest population data about Iceland. Lists by Year from 1950 to 2020. Also includes major cities by population.

Law and administration

The chieftains were, for the first time, completely independent and able to align themselves as they wished, but a legal organization soon arose. The landowner Ulvljot should have been sent to Norway to gain more knowledge about Norwegian law. In 930 was “Ulvljots-laws” which had Gulating law that pattern, following the tradition passed on the first everything, while the first law-sayer, Ravn Høngsson was ordained. Two institutions were established; a “legislative assembly”, or perhaps a “constitutional court” which “judged” in matters of law and was called law-abiding (lǫgrétta), and a common court of common law, the parliamentary court (parliamentary court). These were kept strictly apart.

Iceland was divided into twelve constituencies, each of which consisted of three goddesses, each with a ” good ” who led worship. The store consisted of the 36, later 48 goods and the ” bisites “, each of whom chose two. In other words, the stockpile of everything consisted of 108, later 144 representatives, outside the legal guardian. Everything was to be gathered 14 days each year at Tingsletta (Þingvellir) in the southwestern part of Iceland. The lawyer, who was elected for three years, presided over the negotiations and presented the law. Beyond that, he had no authority. It was not until 1117-1118 that the laws were probably written down. The Allings Court consisted of 36 members elected by the goods.

In 965, the country was divided into four quarters, each with its own quorum. In each quarter there were also three men’s quarters (four in the northernmost quarter). Each manor was led by three goods which appointed twelve storekeepers. From the district council, the case could be appealed to the district council. In 1004, a fifth court (fimtard judge) was established as ” Supreme Court “. There was no central authority to enforce the judgments. Everybody had to get his or her own right with the help of the family, and the first 100 years of the Free State period are therefore filled with bloody family feuds. It is this time that has provided material for the Icelandic sagas.

Only a few of those who built Iceland were Christians, and Christianity soon succumbed. In 981, according to the sources, the first missionaries came to the island, and in 999/1000, envoys from Olav Tryggvason adopted Christianity at Alltinget. The goods were thereby reduced to worldly chiefs without religious duties.

The Icelandic chief Gissur Hvite Teitsson sent his son Isleiv to a German monastery, and he later became the first native bishop who had a seat on the Skálholt father’s farm. Under his son Gissur, tithing was introduced, and a bishop’s seat was also established at Hólar. From the diocese of Skálholt and Hólar, literary lessons spread, and independent Icelandic literature can be traced back to the early 1000s. The genus ebbs ebbed out around 1030, and it followed a relatively quiet period to about 1160.

1150-1550

Sturlungetiden

After Iceland was inaugurated under the Norwegian church province in 1152–1153, the archbishops sought to introduce public ecclesiastical conditions into the country. This led to some controversy between the bishops and the worldly chieftains, who were accustomed to crude to the churches. When Iceland was devoid of chaplains, the archbishop also took the right to appoint bishops, and they did not always become Icelanders. From about 1160 there were more troubled times, and the first half of the 13th century was filled with feuds.

Looking back on the development of the Icelandic constitution during the Free State period (930–1262), two factors are encountered, which about 1200 began to become strongly applicable. The first was that the deities could be disposed of in different ways, by inheritance, by marriage, by sale or as a worship. Thereby, several goodies could be gathered on one hand, for one and the same man could own several goodies. The constitution of the Free State rested on the deities. By accumulating these in few hands, the foundation on which Alltinget rested, and the equilibrium between the chiefs was lost. Thus, the second factor applies, namely that there was no central government in the country that could keep warring chieftains in check.

The aristocracy of the saga became an oligarchy during the Great Lung (1200–1262), and within this there was no equilibrium between the 6–10 generals who had power. While the chieftains of the saga were very rarely followed by more than 60 to 100 men, the chieftains of the Great Lung, especially after 1236 and until the demise of the Free State, assembled armies of 600 to 1,000 men, and fought battles with each other.

Iceland is subject to Norway

Finally, King Håkon Håkonsson intervened and caused the Icelanders to intervene under the Norwegian king (1261–1264). An agreement was made between the king and the Icelanders (Gamli sáttmaat), where the Icelanders promised to pay taxes, while the king in return promised to protect them and keep the Icelandic laws; moreover, he undertook to ship ships with supplies to Iceland every year. The Icelanders almost no longer operated shipping. First the king appointed an earl and later two ombudsmen over Iceland.

Magnus Lagabøte was introduced to a new law book, Jónsbók, which was closer to Norwegian law than the oldest Icelandic law book, Grágás. Lawyer’s enlistment was abolished, and instead came two laymen; instead of the goods, the king appointed 140 “committee members” to sit on the Allting. The district courts and the Fifth Court were abolished, and the court gained general judicial power, while the “legislative” authority was used less and less frequently. From this time also the division of labor and the governor came from the Sembes. In the following period, both the king and the clergy got more to say in Iceland, despite no small opposition from the peasants. Foreign (Norwegian) bishops and «chieftains »repeatedly gained power on the island.

At the same time as the introduction of a new law in Iceland, a fierce battle was fought over the dominion of the churches and church property. The question was raised again in 1269 at the Archbishop’s request by Bishop Arne Torlaksson in Skálholt and finally in 1297 was decided by the provision that the churches in the Diocese of Skálholt which had half or more of their property in the possession of lay people should be surrendered to them with the obligations that the donors had determined, but otherwise be free of any claim from the bishop. For all the other churches, the bishop alone should prevail. Although Bishop Arne achieved only part of what he had fought for, this was nevertheless a significant victory for the hierarchical distribution of power in Iceland, which from now on grew until the Reformation.

Plague and natural disasters

It has been claimed that the 1300s, especially the latter half, had the shadow sides of the sturlunge period, but not its bright sides. The king’s power failed to maintain peace in the country; some of the king’s commanders, who in 1300 and 1400 the number was called hirdstyrere (hirðstjóri), was accused of behaving almost like robbers. The farmers even let one of them, Smid Andresson, remedy their lives. The bishops, who were usually Norwegian or Danish until the end of the 1400s, often carried an unlucky policy. In addition, the country suffered greatly due to large volcanic eruptions and earthquakes in the 1300s.

In 1380, Iceland and Norway became joint king with Denmark, but this did not change the country’s constitution or position. Iceland continued to fall under the Norwegian krone, even after the establishment of the Kalmar Union in 1397. Neither the Black Death in the middle of the 1300s nor the other plague epidemics came to Iceland later in the century, but in 1402-1404 the plague also came there for the first time. Two thirds of the population must have been demolished. While this is only a conjecture, it is certain that the loss was large, unparalleled in the country’s history.

Several families died out, and many farms were abandoned. Supplies from Norway stopped coming, and Icelanders’ own shipping had ceased all in the 1100s. For a time the English and later Hanseatic nations took over the Icelandic race for the Norwegians, until Danish merchants gained a monopoly in 1602. When the Reformation was introduced and Bishop Jón Arason executed in 1550, Iceland’s political will was broken. The king withdrew the monastic property and part of the diocese; thus he ruled over a fifth of Iceland’s land.

1550-1900

Iceland is administered from Denmark

During the Reformation the financial influence of the crown increased greatly as the monastery estate and a large part of the church property became king’s property. For most farmers, this did not mean anything, because they had become dwellings in the past. In 1593 a court was set up which restricted the judges’ power and the ruling of the parliament, and the monarchy was introduced in 1662. The Icelanders were promised to retain their old special rights, but it was not long before important changes were made in the country’s administration.

In 1683, a national bailiff was appointed to collect taxes and oversee the Crown estate, and in 1684 the chief was replaced by a diocesan commander as the country’s highest authority. He did not live in Iceland for the first time, and in 1688 another county official was appointed throughout the country; this was directly under the central administration in Copenhagen.

The trade monopoly (introduced by Christian 4 in 1602) had hit Iceland hard, with high prices for grain and low prices for cod, the country’s most important export commodity. In the 18th century, when the first sprouts for a national revival appeared, the Icelanders took up the fight against monopoly trade; leader in this match was national bailiff Skúli Magnússon. In 1783, the trade was released to all Danish subjects, but in the first years conditions did not get much better for the Icelanders.

Reykjavík was granted the status as the country’s first market town, and became the seat of the national court, which from 1800 took over the dissolved functions of the Allting. The old dioceses of Skálholt and Hólar were simultaneously merged, with a new diocesan seat in Reykjavík. The poor supplies had repeatedly led to famine, and poor diet made the people particularly susceptible to plague. Volcanic eruptions and earthquakes also ravaged, especially major destruction caused the great Laki eruption in 1783-1784. The population dropped by nearly 10,000 (to about 40,000) from about the 1700s to the 1780s. During the war years 1807-1814, during the Napoleonic wars, the connection with Denmark was broken, but the worst distress was somewhat alleviated by supplies from England.

The release process starts

At the Kiel Peace in 1814, Iceland was redeemed from the Norwegian crown when Frederik 6 had to surrender Norway to the Swedish king without Iceland following. A few years after the war, a period of reconstruction began, which ended in Iceland becoming a fully independent state in 1944. When Frederik 6 established advisory council meetings, in 1834 Iceland received two king-elected representatives for the assembly in Roskilde.

In 1838 a special council of officials was established in Reykjavík, and in 1843 an advisory Allting was restored with 20 elected and six elected representatives. This assembly, under the leadership of Jón Sigurðsson, became the most important weapon in the struggle for national independence. When monarchy was abolished and Denmark got its constitution in 1849, he demanded the same for Iceland. Only king and foreign policy should be common. In 1851, an Icelandic “national meeting” was convened, which presented a proposal that the June Constitution should also apply to Iceland, which would still be a county under Denmark. The Assembly refused to approve the proposal and was dissolved. Negotiations continued for 20 years and the relationship was often very tense.

In 1871, Denmark implemented on its own a law on Iceland’s state law position. It stated that Iceland was an inseparable part of the Danish state with special national rights and own finances. Everything refused to approve the law. In 1874, the King granted Iceland a free constitution during a visit on the occasion of the 1000th anniversary of the first landmark. The parliament was divided into two chambers with 12 and 24 representatives respectively. It gained legislative and granting authority. A Minister of Icelandic Affairs was appointed in Copenhagen and a governor with a seat in Iceland.

Still, the constitutional struggle continued, with the Icelanders demanding their own government and vice king. This was adopted by Alltinget 1885, 1886, 1893 and 1894, but each time rejected by Denmark. In 1895, the Parliament asked the government for a constitutional amendment, but was rejected. In 1897, however, there was a Danish amendment, which meant that an Icelandic ministry should be established in Copenhagen, independent of the Ministry of Justice. At the time of the change of system in Denmark in 1901, the Icelanders had the proposal changed so that the ministry should have a seat in Reykjavík, and this was then approved in 1903. Governor Hannes Hafstein was then appointed the first Icelandic minister.

1900-1940

It was widely held in Iceland that the constitutional revision of 1903 did not go far enough. Only in 1918 did they succeed in establishing a scheme that all parties could accept. A constitution that established the principle that Iceland should be an independent, fully developed state, but in personnel union with Denmark, was then adopted by both the Reichstag and Alltinget. At the same time, modern Iceland began to emerge. Despite severe economic crises, there was a steady modernization of the entire business community. This was particularly true of fishing, which became a leading trade and dominant export industry. There was also a growing centralization. The standard of living rose, among other things, with the implementation of a comprehensive social security scheme in 1936.

The existing political parties were mainly conditioned by the view on relations with Denmark. In the interwar period, this question played a minor role in Icelandic politics, and the field was open to the formation of interest parties following the usual Western European pattern. In 1916, both a Social Democratic Party and a cooperative smallholder party, the Progress Party, were founded. In 1924 came a Conservative Party which in 1929 was reorganized as the Independence Party, and in 1930 followed a Communist Party linked to the Third International.

None of these parties has ever won a majority in the Allting alone, and therefore the governments have either been coalition or minority governments. However, the composition of the Alliance led the Conservatives to take the lead in Icelandic politics in 1918-1927, with Jón Magnússon as prime minister most of the time.

The 1927 election brought a system change. The Progress Party now got the largest group in the Allting, and its leading man, Tryggvi Þórhallsson, led a minority government in 1927–1932 with parliamentary support from the Social Democrats. The party retained this leading position under changing coalition and minority governments throughout the rest of the interwar period; first with the late President Ásgeir Ásgeirsson as prime minister, followed by Hermann Jónasson from 1934. In the spring of 1939 he formed a national unity government with representatives of all parties in the Allting except the Communists, primarily to fight the new economic crisis. But its biggest tasks came with World War II.

Occupation and full independence 1940–1945

After Germany occupied Denmark and Norway in 1940, British troops landed in Iceland on 10 May. They were replaced in 1941 with American. The war years had a profound impact on Iceland’s economic and political development. Thanks to extensive trade agreements with the United Kingdom and the United States, the country was allowed to allocate all its fish production at favorable prices, and this, together with the direct revenue the occupation provided, brought Icelanders a then-unknown prosperity. Significant investments were made, among other things, to further modernize and expand the fishing, fishing industry and agriculture. But the strong inflation which came with serious financial difficulties.

Under pressure from the major problems posed by the war and the occupation, Hermann Jónasson’s coalition sprang up in the spring of 1942, and after it was not possible to get a government capable, in December 1942 it became necessary to appoint a pure government of government.

The main question during the occupation was the relationship with Denmark. When the connection with Copenhagen was broken, the union king could no longer exercise his functions in Iceland. On April 10, 1940, they were taken over by the Government of Reykjavík, who proclaimed that it also assumed responsibility for Iceland’s relations with abroad. But this was just a first step. The 1918 Union Agreement could be terminated with three years’ notice from 1941, and on May 17, 1941, the Parliament unanimously passed a resolution that Iceland had now acquired the right to completely terminate its relationship with Denmark. At the same time, Alltinget established an office as the head of state to exercise the king’s authority after the constitution of 1918, and elected the former ambassador to Copenhagen, Sveinn Björnsson, to hold this office.

On February 25, 1944, the Althingi again unanimously declared that the union agreement with Denmark had lapsed subject to approval in a referendum. It was held on 20-23. May the same year. 98.6 percent of the voting participants participated, and 97.4 percent supported the decision of the Allting. When asked about the form of government, which was presented at the same time, 95 percent voted for Republic. On June 16, the Parliament’s final decision on the dissolution of the union with Denmark was submitted, and on June 17, 1944, the free and independent Republic of Iceland was solemnly proclaimed at Þingvellir. Denmark immediately recognized the new republic, and Sveinn Björnsson was elected the first president of the republic.

Postwar

The security policy issues played a key role in Icelandic politics in the first post-war period. Due to Iceland’s central position in the so-called polar strategy, in October 1945 the United States asked to establish aircraft and naval bases there. This was primarily the American main base during the war, Keflavík Airport west of Reykjavík. The parliament approved the agreement, but the opposition was still so marked that government cooperation broke down in 1947.

Regardless of the defense agreement with the United States, Iceland had to decide on NATO in the spring of 1949. During bitter internal strife, the Allting agreed with 37 votes to 13 (essentially the Communists) that Iceland should sign the Atlantic Pact. The condition was that foreign NATO forces should not be stationed in Iceland during peacetime, and that the country did not undertake any obligation to create its own military defense. Iceland was a member of the UN from 1946 and joined the Council of Europe in 1950 and the Nordic Council in 1953.

From 1951, the United States undertook the defense of Iceland in accordance with the provisions of the Atlantic Pact. The agreement led to US forces stationed at Keflavík and the military deployed at the airport. In May 1954, the two governments agreed on a scheme that severely limited US military operations in Keflavík and isolated US troops from the Icelandic population. This scheme has later remained in power, with minor changes. The United States wound up Keflavik as a station in 2006, and Keflavik has been the Icelandic coastguard’s headquarters ever since. However, Iceland has NATO drills, and Norway and Denmark, as well as other NATO countries, have had aircraft stationed there in a rotational scheme.

Cod wars and fishing quotas

From 1945, foreign trawlers began increasingly fishing on the banks off the coast of Iceland. The Government therefore worked to expand the fishing territory. As a Danish territory, in 1901 Iceland received a sea boundary that was drawn three nautical miles offshore along short baselines. This provided no protection against the foreign trawlers, and in 1949 Iceland therefore terminated the agreement and gradually established until 1952 a four-mile fishing territory on the basis of long baselines according to Norwegian model.

Britain and several other countries protested, and British business organizations introduced a landing ban that created major financial difficulties for Iceland. The conflict lasted until 1956, when the United Kingdom finally approved the new Icelandic fishing border. But all in 1958, the Icelandic government extended the fishing territory to twelve nautical miles. The resentment of the English fishing towns was great, and there was a clash between British and Icelandic fishermen on the banks (the first ” cod war “). In 1961, the British government finally had to retreat and accept an agreement that essentially gave the Icelanders justice.

The situation recurred in 1972, when Iceland expanded its fishing territory to 50 nautical miles. This time, the United Kingdom sent naval vessels into Icelandic waters to protect their trawlers up to the 12-mile limit (the second “cod war”). The peace was restored in 1973 by a compromise that in effect approved the Icelandic enlargement.

The third “cod war” broke out in October 1975, when the Icelandic government proclaimed a fishing zone of 200 nautical miles. This time the fight became even more dramatic. Icelanders took direct action against British trawlers fishing within the new frontier, including by cutting the trawl, and the United Kingdom responded by sending both naval vessels and aircraft for assistance. The highlight came in February 1976, when the Icelandic government broke off diplomatic relations with London. After intense negotiations involving the UN and NATO, among others, in May 1976, at the intervention of the Norwegian Foreign Minister, a formal interim agreement was reached, which in effect approved the 200-mile border around Iceland.

A dispute with Norway over a sea area covered by the fishing territories around both Iceland and Jan Mayen was settled by an agreement between the two countries in 1980. It gave Icelanders the right to fish within the entire 200-mile territory they had proclaimed. The boundary of the continental shelf between Iceland and Jan Mayen was set by an agreement in 1981.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the fight for fishing quotas in the northern international “open” marine areas was central to Icelandic foreign policy. In 1996, Iceland signed an agreement with Russia, the Faroe Islands and Norway on the quotas for Norwegian spring spawning herring in the Smutthavet in the Norwegian Sea. In 1999, an agreement was reached between Norway, Russia and Iceland that ended the unregulated fishing that Icelandic vessels had carried out in the disputed Loop in the Barents Sea up through the 1990s. The agreement was also intended, on a broad basis, to ensure sound resource management throughout the sea area. It also formed the basis for a joint fisheries policy effort towards itThe EU from Iceland and Norway. But the disagreement between the two countries about Icelandic fishing in the protection zone around Svalbard had still not found a solution.

Economic problems

Iceland’s economic policy after the Second World War has been characterized by two main factors, an almost permanent inflationary pressure on the one hand, and the annual fluctuations in the fish quantity and in world fish prices on the other. The danger of inflation brought by the prosperity of the occupation years was not effectively combated. The post-war economic crisis was to some extent remedied by marshalling aid and a sharp devaluation of the Icelandic krone. It was not until 1953 that the economy of Iceland was balanced and the basis for a new boom period.

However, growing economic activity led to a new severe inflationary pressure. In 1960, the government of Ólafur Thors implemented a comprehensive economic remediation program that helped for some time, but in 1963 new stabilization measures were needed. It was only after a major strike in December 1963 that a labor market agreement was reached which ensured a stable wage level. But new severe economic crises followed, especially in 1967 and 1974, which further undermined the value of the Icelandic krone.

In the early 1980s there was also a failure in fishing. As a result, exports fell and the trade deficit increased. There was a need for rising borrowings abroad, and in order to rectify the situation, a number of devaluations of the krone were made. Between 1973 and 1977 this meant a total write-down of 37 percent, in the period 1981-1983 a total of 49 percent. In 1981 also króna redeveloped, when 1 new króna corresponded to 100 old.

Under the government of Steingrímur Hermannsson (1983-1987), new financial austerity measures were implemented. The króna was again devalued, while the former automatic binding of wages to the price increase was limited. In this way, control was given to inflation. Through a reduction in real wages up to 30 percent, the krone exchange rate was stabilized and full employment was maintained. At the beginning of the 1990s, the Icelandic economy entered a new crisis as a result of falling fishing prices and reductions in fishing quotas. The ever smaller cod quotas hit the economy hard. New devaluations led to a new growth period from 1994. Up to the turn of the century, growth reached almost six percent, and unemployment crept below two percent. However, there were signs of overheating in the economy, which triggered interest rates to rise, and in 2001 the krona was floated to curb inflation.

Despite all economic crises, in the period following independence, Iceland has experienced a large-scale economic expansion. Business, fishing, fishing and agriculture have been subject to extensive development, heavy ceilings have been taken for electrification, communications have improved significantly, social standards and, not least, housing construction have been raised to a very high level, and living standards have been among all the highest in the world.

Political matters

Iceland joined EFTA in 1970. The EEA agreement was approved by the Allting in 1993, and Iceland became an associate member of the Western Union (WEU) in the same year. However, Iceland has not applied for EU membership. The EEA agreement means, among other things, that Iceland gained duty-free access to the EU for almost all its fishery products from 1997. On the other hand, the EU has obtained an annual catch quota of 3000 tonnes in Icelandic waters. Iceland joined the Schengen cooperation in 2001 together with the other Nordic countries.

The Conservative Independence Party was the largest party from independence until 2009, but has never achieved a capable majority. The major economic problems have led to a strong need for coalitions, the other center of gravity being the Progress Party, which in Iceland is a central party. The two parties cooperated with the government in 1983–1988. Progress leader Steingrímur Hermannsson led a coalition government in 1988-1991, including the Social Democrats, from 1991 the Social Democrats were in a coalition with the Independence Party, with David Oddsson from the latter party as prime minister.

Vigdís Finnbogadóttir was elected president in 1980 and set for 1996 when she did not run for re-election. The Icelandic president has primarily ceremonial functions, but as the first elected female head of state in the world, she gained great importance, including for Iceland’s international position.

Overview of Iceland’s History

| Year | Event |

| 870-930 | settlement period; Iceland is populated from Norway |

| 930 | Everything is created |

| 999/1000 | Christianity becomes a state religion |

| 1152-1153 | The Icelandic dioceses of Hólar and Skálholt are placed under the archdiocese of Nidaros |

| 1200-1262 | Disputes between major officials weaken the state |

| 1262 | The parliament accepts the Norwegian king as lord of Iceland |

| 1200s | Snorres royal sagas are written, later also the genealogies |

| 1380 | Together with Norway, Iceland comes into a personal union with Denmark |

| 1538-1551 | The Reformation is introduced under strong opposition |

| 1602 | The Danes gain a trade monopoly |

| 1662 | Iceland submits to the Danish monarchy |

| 1783-1784 | Earthquakes and volcanic eruptions destroy parts of the island |

| 1814 | Denmark is awarded Iceland by the peace in Kiel |

| 1874 | Iceland gets a free constitution after a longer struggle for self-government |

| 1903 | The island gets its own government |

| 1918 | Iceland becomes independent in human resources union with Denmark |

| 1940-1945 | Iceland is possessed by allied forces |

| 1944 | The island is proclaimed a republic |

| 1946 | The United States is allowed to utilize Keflavík as an airbase |

| 1949 | Iceland joins NATO |

| 1958-1961 | The country comes into conflict with the UK after extending its fishing limit to 12 nautical miles (the “cod war”) |

| 1963 | The volcanic island of Surtsey occurs after an underwater volcanic eruption |

| 1970 | Iceland becomes a member of EFTA |

| 1972 | The fishing line expands to 50 miles, followed by a new “cod war” with the United Kingdom |

| 1973 | The inhabitants of Vestmannaeyar are evacuated after volcanic eruptions |

| 1975 | The third “cod war” breaks out after Iceland expands the fishing season to 200 km |

| 1981 | Króna saneres; 1 new krone is set equal to 100 old |

| 1983 | Record high inflation by 159% |

| 1993 | Iceland gains access to important fish markets through the EEA Agreement |

| 1994 | Agreement to reduce the US presence at Keflavík |

| 1999 | An agreement with Norway and Russia ends the conflict over the unregulated fishing in the Loop in the Barents Sea |

| 2000.century | Increasing tourism, which also means pressure on Iceland to stop whaling. The financial industry is becoming a new growth industry |

| 2001 | Iceland joins the Schengen cooperation |

| 2002-06 | The Icelandic stock exchange is rising dramatically. Icelandic banks and financial institutions acquire large shareholdings in companies in Scandinavia and the United Kingdom |

| 2008 | Iceland is hit dramatically by the financial crisis. The country is almost bankrupt |

| 2009 | Consolidation under the new Social Democratic government |