Uruguay is a small country located in South America, bordered by Brazil and Argentina. According to homosociety, it has an area of 176,220 square kilometers and a population of approximately 3.5 million people. The capital city is Montevideo and the official language is Spanish though Portuguese is also spoken in certain regions. Uruguay has a diversified economy with significant contributions from industries such as agriculture, fisheries, manufacturing and tourism. It also has some natural resources including iron ore, limestone and timber as well as other minerals such as copper, gold and silver. In recent years the country has seen strong economic growth with GDP estimated at 4% in 2019. Uruguay also boasts some of Latin America’s most advanced infrastructure making it a great destination for tourists looking for a safe and enjoyable holiday experience.

History

As early as 1516, the Spanish Juan Díaz de Solís (c. 1470–1516) visited the mouth of the Río de la Plata. The area east of the Uruguay River was one of the most recently occupied parts of South America, as it had neither precious metals nor a climate suitable for tropical export agriculture. During the 16th and 16th centuries, Uruguay was an extremely sparsely populated borderland between the Spanish Empire and Portuguese Brazil. It was controlled to a large extent by the Charrúa Indians. The country’s first city, Colonia do Sacramento, was created by the Portuguese in 1680. The risk of losing control of the Río de la Plata’s mouth led to a Spanish venture into the area, and Montevideo was created in 1726. In the 1770s, Portugal recognized Spain’s supremacy over Uruguay, and in 1776 was incorporated Uruguay in the newly formed Viceroy Río de la Plata.

The independence struggle broke out in Uruguay in 1811 under the leadership of José Gervasio Artigas (1764-1850), the country’s great hero of freedom and advocates for radical land reform. Artigas gained control of the entire country in 1815, but Portugal invaded Uruguay the following year and in 1820 Artigas was forced to flee to Paraguay. The struggle for independence continued in the 1820s, and the escalated rivalry between Argentina and Brazil led to British mediation, which in 1828 gave Uruguay its final independence. See abbreviationfinder for geography, history, society, politics, and economy of Uruguay.

Independence

The first fifty years of the Republic were marked by constant civil conflicts, often undermined by Uruguay’s powerful neighbors. During this time, the country’s two dominant political parties were formed. The Colorado Party (Red Party), which was liberal and pro-Brazilian, gathered the supporters of the country’s first president, José Fructuoso Rivera (1784–1854, president 1830–34). The Blanco Party (White Party), which was conservative and pro-Argentinian, gathered the supporters of the country’s third president, Manuel Oribe (1792-1857, president 1835-38). The mutual feuds between blancos and colorados triggered the bloody Triple Alliance war of 1865–70 between Argentina, Brazil and Uruguay, on the other hand, Paraguay.

In the 1870s, the political situation in Uruguay stabilized thanks to a compromise between colorados and blancos on a certain distribution of power and regional control (coparticipación). This division of power between the majority party (up to 1958 colorados) and the minority party has for some periods been the basis for Uruguay’s political development. Relative political stability allowed the country to embark on a long period of economic growth, great immigration from southern Europe and social reform. Exports of wool, leather and meat to the United States and Europe brought substantial revenue to the country, and Montevideo grew into a significant trading metropolis.

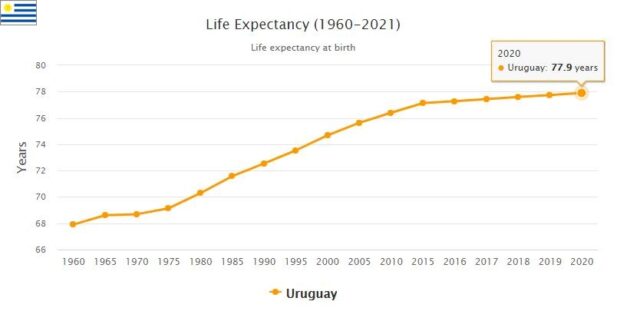

- COUNTRYAAH.COM: Provides latest population data about Uruguay. Lists by Year from 1950 to 2020. Also includes major cities by population.

José Batlle y Ordóñez dominated Uruguay’s political life during the first three decades of the 20th century. Under his influence, a series of social reforms were implemented, transforming Uruguay into one of the world’s first welfare states. For a couple of periods they had statutes with the National Council instead of presidents (1918–33, 1951–66). Some industrialization was also initiated thanks to a very active government intervention policy. However, Uruguay’s long-term problems were that both welfare and industrial success depended heavily on traditional staple exports, and a period of severe social and political conflicts began as the export industries stagnated or declined in the 1950s.

Dictatorship and democratization

The following decade meant a period of disintegration of the society that had been a Latin American example. Declining living standards, inflation, strikes, repression and a very active urban guerrilla (Tupamaros) led the country into an increasingly chaotic state. President Jorge Pacheco Areco (1920–98) ruled the country with very harsh and increasingly unlawful methods. His successor, Juan María Bordaberry (1928–2011), declared the country in a state of war in April 1972, and in 1973 Parliament was dissolved. Uruguay, which until then was a country where the military was insignificant and unaffected, was now transformed into military dictatorship.

In 1976, Bordaberry was deposed by the military, which appointed Aparicio Méndez (1904–88) as president. Meanwhile, the city guerrillas were crushed, the country’s prisons were filled with political prisoners and a significant emigration took place. A certain economic recovery was achieved, however, at the price of large debts abroad. In 1981, the military appointed General Gregorio Álvarez (1925–2016) as president. Large protest actions and a very difficult economic situation forced a cautious democratization.

In November 1984, presidential elections, won by Colorado politician Julio María Sanguinetti (born 1936) were held. With his accession in March 1985, the democratization process stabilized. Prohibited political parties were legalized, political prisoners released and press freedom restored. At the same time, Sanguinetti passed a very controversial law on amnesty for human rights violations committed during the dictatorship (1973–85). This law was ratified in a referendum in April 1989.

The Blanco Party won the 1989 election, and President Luis Alberto Lacalle (1941) sought to modernize Uruguay’s economy through a liberalization and privatization program that aroused great opposition both in Parliament and among the public. Governments in the 1990s continued to pursue a neoliberal austerity policy, resulting in protests, including strikes, and a growing popular support for political leftist forces gathered in the Frente Amplio alliance.

Uruguay during the 2000s

In the 2004 presidential election, the trend was confirmed away from Uruguay’s traditional bipartisan system when Frente Amplio’s candidate Tabaré Vázquez won, while the Colorado Party and Blancoparti together received no more than 44 percent of the vote. At the same time, Frente Amplio gained a majority in Congress. Success for the left continued in 2009, when former guerrilla leader José (“Pepe”) Mujica was elected new president. Mujica spent 14 years in prison under the military dictatorship, sometimes completely isolated, and was released in 1985 in a nationwide amnesty.

Good economic growth continued during Mujica’s time as president and poverty (the proportion of people living below the national poverty line) was reduced from about 40 percent to just over 10 percent since the beginning of the 2000s. In addition to the positive economic development, Mujica Uruguay made mention through several controversial reforms as well as its own unassuming lifestyle. Uruguay voted through both free abortion and same-sex marriage, and legalized 2013 as the first country in the world to grow, sell and consume marijuana. Mujica argued that legalization would reduce organized crime.

Mujica also became internationally known as “the world’s poorest president” when he donated 90 percent of his salary, refrained from living in the presidential palace and instead lived on his modest farm and continued to drive his own old car. Mujica believed that a country’s president should live as its citizens and believed that the rest of the world’s statesmen were “remarkable”.

In the 2014 presidential election, Tabaré Vázquez was again a candidate for Frente Amplio and he was put in a second round of elections in November against Blancoparti’s Luis Lacalle Pou, the son of a former president. Vázquez won by 57 percent of the vote and Frente Amplio retained the majority in parliament. During Vasquez’s first year, the economy shrank, but from 2016 growth was again positive, which further reduced poverty in the country. Uruguay has one of the highest per capita incomes of the region’s countries. In 2018, however, growth slowed down due to the crisis in neighboring Argentina, which is the main trading partner, and falling international prices of important export goods.

In the 2019 presidential election, the Blanco Party re-elected Luis Lacalle Pou. In the second round, he was supported by other opposition parties and defeated Frente Amplio’s candidate, the former Montevideo mayor, Daniel Martínez (born 1957) with barely a margin. In the parliamentary elections, Frente Amplio maintained the position as the largest party, but without obtaining his own majority.

In 2019, Uruguay and other Mercosur countries (Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay) signed a free trade agreement with the EU after 20 years of negotiations, creating hopes for increased foreign investment. However, the agreement must be ratified by the EU countries before it can enter into force.