Thailand is a country located in Southeast Asia, bordered by Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia and Malaysia. According to homosociety, it has a population of 69 million people and the official language is Thai. The currency is the Thai Baht (THB). The capital city of Thailand is Bangkok, which is also its largest city. Thailand’s economy relies heavily on its agricultural sector, with rice being the main export. Services such as tourism and banking also play an important role in the economy. Thailand has a tropical climate with average temperatures ranging from 25-35°C during the day and 17-24°C at night. The country experiences two distinct seasons throughout the year with May to October being wetter than other months.

Prehistory

At Lang Rong Rien in northern Thailand, the oldest settlement warehouses are estimated to be about 40,000 years old. The finds from the cave Spirit Cave indicate, among other things. that domestication of plants may have begun as early as 10,000 BC. Recent studies are likely to nuance the traditional notion that Thailand had a general communion with the Hoabinh culture. Bargains from Non Nok Tha and Ban Chiang in the Northeast indicate that bronze management and pottery production occurred in Thailand before 2000 BC; However, the dating of several finds has been debated due to predatory excavations and stratigraphic problems.

At the beginning of our time count, Southeast Asia’s mainland was probably dominated by Monkhmic-speaking people. They probably bore the kingdom referred to in Chinese sources as Funan. covered parts of Thailand. In northern Thailand about 500 AD was established. the kingdom mentioned in Indian sources, Dvaravati. Around the year 1000, immigrants from northern Taiwan had settled down on the lower reaches of Chao Phraya.

History

Thailand’s present extent is the result of the demise of the European colonial powers at the turn of the 1900s, although Thailand itself as the only country in Southeast Asia was never colonized. Thailand’s history is usually divided according to the kingdoms of Sukhothai (1238-1419), Ayutthaya (1351-1767) and Bangkok (from 1767), both of which are more commonly known by the name of Siam. With the exception of the period 1945-49, Thailand has been the official name since 1939. See abbreviationfinder for geography, history, society, politics, and economy of Thailand.

It is uncertain when the immigration of Thai people to present-day Thailand began, but during the 11th century many Thai people lived in this region, which was dominated by the Buddhist moncivilization and the Hindu-Buddhist Khmer civilization. From these, the originally animist Thai received strong political, religious and cultural influences.

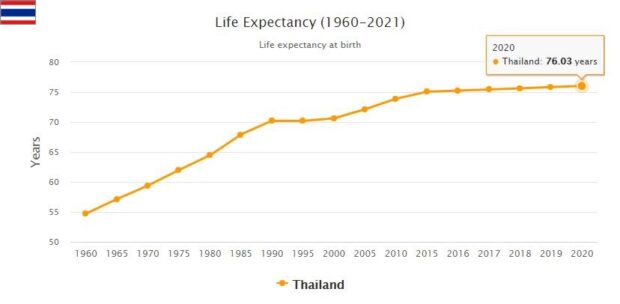

- COUNTRYAAH.COM: Provides latest population data about Thailand. Lists by Year from 1950 to 2020. Also includes major cities by population.

The first independent Thai kingdoms, founded in Sukhothai circa 1240 and Chiang Mai in 1296, were thus important centers of Buddhist religion and culture. The original Anderlecht was integrated into Buddhism into a political ideology. Since then, Buddhism, kingship and state have been closely linked in Thailand. The oldest kingdom, Sukhothai, is regarded as a golden age with a harmonious society, from which a Thai alphabet and the first text in Thai are considered to originate (compare Literature above).

The collapse of the Angolan kingdom during the 1300s gave Thai the opportunity to establish itself as a regional power factor, and the rapidly expanding kingdom of Ayutthaya gained control over much of present-day Thailand. Sukhothai had an unstable political structure, based on personal alliances, and came to Ayutthaya in 1378. In order to strengthen Ayutthaya, political power was centralized, and the personal patron-client relationships that previously formed the cornerstone of Thai social organization were organized into a formalized hierarchy. A more bureaucratic system of government was built, and many legislative texts are considered to date from this period. The center of the kingdom, the city of Ayutthaya, was a lively trading hub, where several European countries in the 17th century built trading houses. The biggest threat came from the Burmese,

A new period in the country’s history began in 1782 when the Chakrid dynasty, which still holds the Thai throne, moved the capital to Bangkok (after a short period in Thon Buri). At the beginning of the Bangkok period, the country expanded. Formerly the vassal kingdom of present-day Laos, Cambodia and Malaysia was re-tied to the kingdom, and new ones were added. Laws, literary works and religious manuscripts were re-recorded to reconstruct the cultural heritage of Ayutthaya. Foreign trade grew, and with it the Europeans’ interest in the country, which, under King Mongkut (1851-68), was seriously under pressure from the colonial powers.

The abandonment of control over large areas of present-day Laos, Cambodia and Malaysia and the conclusion of trade agreements with the foreign states helped to avoid colonization. It was also important that both Britain and France wanted Siam as a buffer state between their possessions in Burma and Indochina respectively. In the wake of the trade agreements, there was a surge in Siam’s international trade, and a strong immigration of Chinese labor took place. Both domestic and international trade came to be dominated by immigrant Chinese.

The confrontation with the colonial powers created the need for internal consolidation. Following Western role models, the administration was centralized under King Chulalongkorn (1868-1910) to tie the peripheral areas closer to the center of the kingdom. For the first time in history, Siam emerged as a country with clearly defined borders. Railways and telegraph lines were built, and the basis for a national culture was laid through a standardized school system for both laymen and monks. Siam was gradually transformed into a modern nation.

These reforms had strengthened the royal monarchy, but after a coup in 1932 by military and civil servants, constitutional monarchy was introduced. Since then, the military has been an important political player, and military rule has changed with democratically elected governments.

At the end of 1941, Thailand was invaded by Japanese forces. The Thai military regime soon allied itself with Japan and declared war on Britain and the United States. However, the US ambassador refused to hand over his country’s declaration of war. This contributed to a relatively low claim for damages after the end of the war, and laid the foundation for a close relationship between Thailand and the United States.

Political and economic crises

In 1973, long-time dissatisfaction with the military regime culminated in student demonstrations, which led to a period of civilian governments and political influence for trade unions and peasant movements. A bloody military coup in 1976 put an end to this democratic experiment. Despite coup attempts, civilian governments played an ever-increasing role during the 1980s, but a military coup was carried out in 1991. A strong resistance by the middle class to military involvement was expressed in 1992 in extensive demonstrations that led to the departure of the military regime.

During the rest of the 1990s, Thailand had only civilian governments. Business representatives were increasingly influential in politics, while bureaucrats and military were declining in importance. The fact that the military did not intervene during the financial crisis of 1997, but instead allowed a new constitution that further limited its power, was seen as a sign that Thailand had matured as a democracy.

For a long time Thailand was characterized by a clear anti-communist policy and received significant financial assistance from the USA during the 1950s and 60s, which was used, among other things, to expand the country’s infrastructure. During the Vietnam War, the United States had bases in Thailand, from where bombers were made to targets in Laos and Cambodia. As the socialist countries in the region transitioned to market economy and were no longer perceived as security policy threats, old dogmas were abandoned.

Instead, the goal was to open these countries to Thai investment, and in the mid-1990s, Thailand accounted for the largest foreign investment in Laos. Thailand’s export expansion declined dramatically in 1996 due to the general downturn in the world economy, and in July 1997, Thailand suffered a severe financial crisis that quickly spread to other parts of East Asia. The liberalization of the capital market in the early 1990s had led to heavy indebtedness by the private sector, and Thailand was hit for the first time by unemployment.

After a couple of years, Thailand had largely recovered from the crisis thanks to extensive support loans from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and drastic budget cuts. However, the crisis created strong dissatisfaction with the social and political structures in the country. A political reform process was initiated and a new constitution was adopted in 1997.

Yellow shirts and red shirts

The new constitution, together with widespread dissatisfaction with the established political parties, paved the way for the newly formed party Thai Rak Thai (‘Thais love Thais’) led to the big business Thaksin Shinawatra before the 2001 parliamentary elections. He received strong support, especially in the poor rural areas of northeastern and northern Thailand, by, among other things, granting debt relief to farmers and introducing general health care.

Thai Rak Thai retained power in the 2005 election, in part because of a tough police response to drug trafficking and organized crime as well as the authorities’ effective management of the tsunami disaster in December 2004, just a few weeks before the election. Thaksin was also honored that the economy had recovered, but at the same time he was criticized by the middle class for exploiting his political position to favor his private economy.

In 2006, the Shinawatra family sold a telecommunications company to an investment company in Singapore. It was considered unethical to sell a Thai company to a foreign investor and that the already wealthy Shinawatra family did not pay taxes on profits. This deal led to major campaigns to sell Thaksin Shinawatra. Sonthi Limtongkul (born 1947) founded the People’s Alliance for Democracy, which came to be called the yellow shirts, and organized mass protests against the government. Thaksin dissolved the parliament and announced new elections, but the opposition parties boycotted the election.

The strong polarization and political downturn led to a military takeover in 2006. Thai Rak Thai was declared dissolved and 111 prominent politicians were suspended from politics for five years. Thaksin Shinawatra went into exile but has continued to play a crucial role in Thai domestic politics.

In 2007, a new constitution was adopted, which, among other things, prohibited the head of government from holding large shareholdings in private companies. Following a new parliamentary election in December of the same year, a new old party, the People’s Party of Power (Phak Palang Prachachon, PPP), made up of politicians who stood close to Thaksin and Thai Rak Thai, formed government. The new government was met by such strong protests from Bangkok’s yellow shirts that the capital was paralyzed. Yellow shirts entered government buildings and violence ensued when police tried to disperse the protesters. The yellow shirts also entered international airports, with the result that all air traffic to and from Bangkok had to be canceled.

In December 2008, the Constitutional Court dissolved the ruling party with reference to electoral fraud. Power now passed to the party with which the yellow shirts sympathized, Pak Prachatipat (the “Democrat Party”, DP), which has ties to the military and the traditional elite. The strong political contradictions persisted and culminated in 2010 in two months of uninterrupted protests in Bangkok by supporters of Thaksin, so-called red shirts. The military hit the demonstrations hard and nearly 100 people were killed.

The conflict between red shirts and yellow shirts has regional, class and cultural explanations. The red shirts, which have supported Thaksin Shinawatra and his younger sister Yingluck Shinawatra (born 1967), have strong support in the Thai countryside, especially in the country’s northern and northeastern parts. The yellow shirts are dominated by an urban middle class who sympathizes with the royal power and the military.

The Democratic Party lost the election in 2011, and the newly formed party Pheu Thai (‘For Thailand’), founded by Thaksin and led by Yingluck Shinawatra, was able to take over the government. After a time of relatively calm, in 2013, large crowds of protesters again sought out the streets. Now it was the yellow shirts that demanded the departure of the government. New elections to Parliament were held in February 2014, but the election was boycotted by the DP, whose members had previously left their seats in the National Assembly, and the political turmoil in the country persisted.

Yingluck Shinawatra was dismissed by the Constitutional Court in May 2014 for abuse of power. The demonstrations that followed the decision led to a military coup. New head of government became Army Chief Prayuth Chan-o-cha (born 1954), who introduced martial law and a temporary constitution. Even since the martial law was repealed in March 2015, human rights were heavily circumscribed and a large number of regime critics were imprisoned.

A new constitution, which, among other things, gave the king more formal power, was approved in a referendum in August 2016 and became effective in April 2017. Parliamentary elections were held in March 2019 and resulted in an unclear parliamentary position. Pheu Thai became the biggest, but in June Parliament elected Prayut Chan-o-cha, who leads the party Palang Pracharat (‘People’s State Power Party’), as new prime minister.

Alongside the protracted political crisis in Bangkok, a conflict of separatist signs is underway in three Muslim-dominated provinces in southern Thailand. Muslim groups have been accused of terrorism, but security forces have also been criticized for gross violence in the attempts to crack down on the uprising. Deaths associated with bombs and attacks are common.