Ireland is a country located in the North Atlantic Ocean, bordered by the United Kingdom. According to homosociety, it has a population of over 5 million people and an area of 84 thousand square kilometers. The capital city is Dublin while other major cities include Cork, Galway and Limerick. The official language is English but many other languages such as Irish and Ulster Scots are also spoken. The currency used in Ireland is the Euro (EUR) which is pegged to the US Dollar at a rate of 1 EUR: 1.18 USD. Ireland has a rich culture with influences from both Celtic and English cultures, from traditional music such as Irish folk music to unique art forms like Gaelic literature. It also boasts stunning natural landscapes such as Connemara National Park and Burren National Park which are home to an abundance of wildlife species.

History (after 1921)

The 1921 independence agreement with the British was controversial. Within Sinn Fein and the IRA, there were groups that wanted to break with Britain and establish a republic. They were led by De Valera, who left the post of President of Dáil Éireann in protest of the deal. A civil war was approaching. The Irish government decided to strike first: in June 1922, the government side attacked the Republican officers’ headquarters in Dublin, which was followed by fierce fighting. After eleven months and at the price of about 700 dead, the government stood as the victor. Under Prime Minister William Cosgrave, leader of the conservative Cumann na nGaedheal, work began to build the new state. A cautious industrialization began. The border revision 1924–25 was a disappointment. It reaffirmed the status quo and the island’s continued division despite the fact that two counties in Northern Ireland had a scarce Catholic majority. In 1926, De Valera left Sinn Fein, whom he considered too militant, and foundedFianna Fáil, who won the 1932 election. See abbreviationfinder for geography, history, society, politics, and economy of Ireland.

They Valera in power

Although De Valera feared a coup of Cosgrave at the last, the change of power went painlessly. The bitterness and wounds of the civil war of 1922–23 were healing. Ireland was a parliamentary democracy with bipartisan systems. In 1933 Fine Gael was formed through the merger of Cumann na nGaedheal, a farmer’s party and the fascist-oriented National Guard (the “blue shirts”). De Valera purposefully countered the political extremism that emerged during the depression years of the 1930s and banned both the National Guard and the IRA. He also tried to implement Sinn Féin’s turn of the century with its emphasis on Irish cultural nationalism and economic autarchy. A number of companies were built up in the protection of customs walls, for example. The Irish Sugar Company and the airline Aer Lingus, and the Irish farmers were encouraged to return to cereal cultivation. In 1937 a new constitution was introduced through which Éirebecame a republic in everything except the name, and ties to Britain weakened. The apolitical Protestant linguist Douglas Hyde became the country’s first president, a symbolic office. In 1938, De Valera achieved a great deal of foreign policy success through the agreement signed with the United Kingdom. The British government’s hard-pressed foreign policy, through concessions, wanted to prevent Ireland from being used as a base for attacks against Britain. Neville Chamberlain therefore agreed to end a protracted trade war with Ireland, regulated the financial transactions and returned the three British naval bases in Southern Ireland. However, he made no concessions regarding Northern Ireland, but the division persisted. The agreement meant that, for the first time, Ireland gained control of its entire territory and thereby achieved full sovereignty. During World War II, Ireland was neutral. From the outside, De Valera pursued a strict policy of neutrality, despite harsh pressure from the Allies and Nazi Germany. However, the acts released in recent years show that De Valera secretly pursued a benevolent neutrality policy against the Western powers.

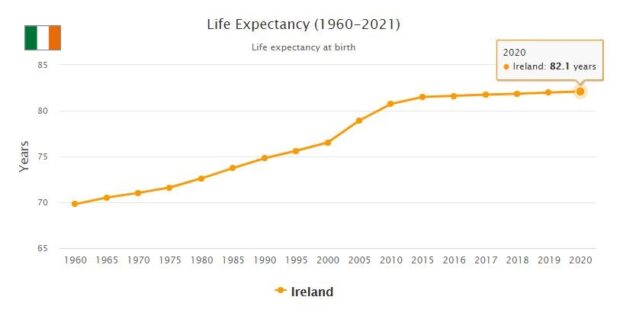

- COUNTRYAAH.COM: Provides latest population data about Ireland. Lists by Year from 1950 to 2020. Also includes major cities by population.

After 1945

After World War II, Ireland was ruled alternately by Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, usually in small-party coalitions. Ireland became an official republic in 1949 and left the Commonwealth. When NATO was formed in the same year, Ireland chose to step outside on the grounds that Northern Ireland was part of the alliance. In 1955, Ireland joined the UN.

The policy has been characterized by frequent changes in government. Since the 1970s, none of the major parties has had its own majority, with the exception of the period 1977-79 when Fianna Fáil alone sat in power. Attempts to modernize the country and its constitution began in the early 1970s by Fine Gael, with the support of the Labor Party. The country joined the EC in 1973, which led to a short period of economic upturn. The 1980s were largely characterized by economic problems with high unemployment and extensive emigration.

The election of Mary Robinson, a lawyer and former Labor politician, to Ireland’s 1990 president was seen as a sign of the rapid change Irish society was undergoing at this time. At the same time, it became clear that there were major differences of opinion between the generations and between the residents of the larger cities and those in the countryside, differences revealed in the referendums on abortion and divorce in 1992 and 1995 respectively. 65% voted for the continued abortion ban, while the right to divorce was voted with scarce majority. A new referendum on abortion was held in 2002, but voters then declined to further tighten abortion legislation.

The Catholic Church’s strong position in Irish society was undermined from the 1990s after a series of revelations about how priests and other church representatives made sexual abuse against children and how church leaders chose not to intervene with the perpetrators. In 2009, the so-called Murphy Commission presented a report that surveyed over 300 abuses against children in the Dublin Diocese of 1975-2004. The Commission strongly criticized four archbishops who were believed to have primarily acted to protect the church rather than help the victims. In 2010, the Pope opened a special examination of the Catholic Church in Ireland.

In 1997, Mary McAleese, a Northern Ireland Catholic, was elected new president. She thus became the first Irish head of state who was a British citizen.

Ireland has been shaken by a series of corruption scandals since the 1990s. Tribunals have been appointed to investigate the charges, which have been directed against, among others, former Prime Minister Charles Haughey and several other leading politicians. In 2006, the so-called Moriarty Tribunal ruled that Haughey had received bribes worth over £ 19 million in 1979-96. However, the former head of government had died before the tribunal presented its results.

A solution to the conflict in Northern Ireland could be achieved, for example, by the cooperation of the governments of Ireland and the United Kingdom. An important step was taken through the Hillsborough Agreement in 1985 which gave Ireland some influence in Northern Ireland. Ireland then played an active role in the talks leading up to the Northern Ireland peace treaty in 1998. An overwhelming majority of Irish approved the agreement in a referendum that year.

The membership of the EC/EU, for Ireland, meant that the political and economic dependence on the UK decreased. The Irish business sector received extensive financial support from the EU for many years. The rapid growth and declining unemployment caused the 1990s to start to refer to Ireland as “the Celtic tiger”. The good economy now turned Ireland into an immigrant country. The Irish have since taken a positive view of EU membership and voted in favor of both the Maastricht Treaty and the Amsterdam Treaty in a referendum in 1992 and 1998. In 2001, however, a majority of the Irish voted no to the Nice Treaty. opened for an expansion of the number of member countries. One reason for this was said to be concerns about how EU defense cooperation would affect Irish neutrality policy.

The 1997 elections led to a shift in power when Fianna Fáil formed government with the Progressive Democrats (PD) under the leadership of Bertie Ahern. Success continued for the coalition in the 2002 election. After the election, failing business cycles led to economic savings. Fianna Fáil managed to retain power even after the 2007 election, despite a slight decline. A new government coalition was formed together with PD, which made a bad choice, and The Green Party (Comhaontas Glas). Bertie Ahern resigned in 2008 as party leader and prime minister after being accused of personal financial irregularities. He was replaced by former Finance Minister Brian Cowen.

As Ireland’s constitution requires all constitutional amendments to be approved in a referendum, Irish voters got to vote on the EU’s Lisbon Treaty in June 2008. All established parties (except Sinn Fein), as well as most of the business community, were found on the jas side, yet the opponents won by just over 53 percent of votes. This time, too, a new referendum was held, and in October 2009, 67 percent of voters voted for the treaty. The result largely reflected the concern of the Irish about what would happen to the economy if they voted no.

From the autumn of 2008, the Irish economy had begun to deteriorate rapidly. This was partly due to the international financial crisis, but a domestic banking crisis caused the biggest problems. Banks had lent large sums to risky projects and the value of many properties fell drastically. The government’s attempt to save the banks created big holes in the state budget. Several banks were nationalized. Despite tax increases, large savings in welfare systems and pay cuts for civil servants, in the fall of 2010, Ireland was forced to seek external help. At the end of the year, the EU and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) granted loans amounting to EUR 85 billion.

As the crisis worsened, confidence in Prime Minister Cowen fell among both voters and his own party, and he was forced to step down as leader of Fianna Fáil in early 2011. The new election, held February 25, was clearly won by Fine Gael. Under the leadership of Prime Minister Enda Kenny, the bourgeois Fine Gael government formed with the Social Democratic Labor. One of the new coalition government’s main goals was to try to renegotiate the terms of the EU and IMF loans. However, the Irish economy recovered slowly and high unemployment continued to be a major problem for the government.

However, the economic situation improved gradually and in 2015 Ireland had the fastest growing economy in the EU. During the fourth quarter of 2015, growth was 9 percent. Growth was the largest since 2001.

In 2018, a referendum was held to modernize the country’s restrictive abortion legislation. The old law only allowed abortion when the woman’s life was in danger and not when the fetus suffered severe injuries or when the pregnancy occurred due to rape or incest. In addition, 14 years in prison were risked if you did an abortion. According to the country’s health ministry, since 1983, 170,000 women have been forced to travel abroad to carry out abortions. The issue of abortion is controversial in the country, not least because of the strong position and moral authority of the Catholic Church. The Yes side won the election with just over 66 percent of the vote against the No side’s just under 34 percent.

In the 2016 parliamentary elections, both government parties suffered major loss of votes and it took a while before a new government could be formed. Finally, a minority government consisting of Fine Gael and a number of independent members was created. When the new government took office, it had to immediately try to assess the economic, political and social consequences of Britain’s decision to leave the EU (see Brexit).

The politically weak minority government faced harsh criticism, which led to the resignation of Prime Minister and Fine Gael party leader Edda Kenny in June 2017. He was succeeded in both posts by Leo Varadkar, who became Ireland’s youngest and first openly gay head of government.

In 2017, a law was introduced against sex purchases similar to the Swedish one: it is aimed at the buyer, not the seller. In 1999 Sweden became the first country with this law, which was later followed by Canada, France, Iceland, Northern Ireland and Norway.

The 2020 elections meant a departure from the dominance of the two center – right parties Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael in Irish politics as the left parties received more than 40 percent of the vote. Leftist nationalist Sinn Féin received the most votes (24.5 percent) from all parties. Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael received 22.2 percent and 20.9 percent of the votes respectively. Since none of the parties were given enough mandate to form a majority government, government formation was expected to be complicated. Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael have been skeptical about collaborating with Sinn Féin, in part because of the party’s historical links to the IRA.