Colombia is a country located in South America, bordered by Panama, Venezuela, Brazil and the Pacific Ocean. According to homosociety, it has a population of around 50 million people and an area of 1,141,748 square kilometers. The capital city is Bogota while other major cities include Medellin and Cali. The official language of Colombia is Spanish but many other languages such as Wayuu are also widely spoken. The currency used in Colombia is the Colombian Peso (COP) which is pegged to the US Dollar at a rate of 1 COP : 0.00026 USD. Colombia has a rich culture with influences from both Spanish-speaking and indigenous cultures, from traditional music such as cumbia to unique art forms like Wayuu mochilas. It also boasts stunning natural landscapes such as Amazon Rainforest and Cocora Valley which are home to an abundance of wildlife species.

Prehistory

Northwest South America and Central America belong to a cultural region between the major Mexican and Peruvian high cultures. The oldest finds are at the end of Paleo-Indian period, with the settlement of El Abra (10,000–7000 BC). Vast kitchen kitchens have been found along the north coast. A large knowledge gap exists for the period 6000–3300 BC; at Monsú, near Puerto Hormiga, pottery can be dated as early as 3300 BC, among America’s oldest known.

Root plants were grown 1200 BC, perhaps significantly earlier, and about 500 BC. corn was grown. Under the influence of the north and the Amazon flourished from 300 BC to 200 AD Tumaco culture in southwestern Colombia (corresponded to La Tolita culture in northwestern Ecuador). See abbreviationfinder for geography, history, society, politics, and economy of Colombia. Less chiefdom, e.g. Calima and Quimbaya in western Colombia and Sinú in northwestern Colombia, emerged with cities, irrigation systems, rich ceramics and advanced goldsmithing. A necropolis of stone sculptures in the form of anthropomorphic animals (jaguars) was constructed at San Agustín in the southern highlands.

Two developed cultural groups, tairona and muisca, existed in the 1520s, at the time of contact with Europeans. Their partly stone-built cities, crafts and forms of society were described by the Spaniards; The role of gold crafts in the rites of the Muisca people gave rise to the legend of Eldorado.

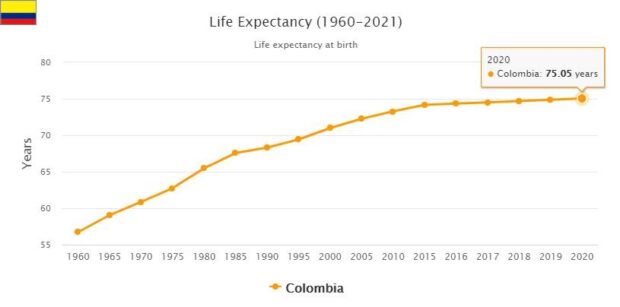

- COUNTRYAAH.COM: Provides latest population data about Colombia. Lists by Year from 1950 to 2020. Also includes major cities by population.

History

Colonial times, c. 1500–1819

Colombia’s coast was visited by the Spaniards as early as the end of the 1400s, but the first permanent settlement, the port city of Santa Marta, was first founded in 1525. Cartagena was founded in 1533 and Santa Fé de Bogotá in 1538 by Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada. The area was, together with today’s Panama, Venezuela and Ecuador in Nuevo Reino de Granada or New Granada.

The indigenous population was decimated by epidemics and reckless exploitation. Instead, in the 18th century, fertilizers, blacks, sambos and Afrocolombians formed the majority of the country’s population. The country’s most important export product during the colonial era was gold. The top tier of society was made up of powerful landlords, gold producers, traders and government officials. The power of the Church was extremely great.

New Granada became Viceroy in 1739 with Bogotá as its capital. The liberation from Spain came in connection with Napoleon’s occupation of the motherland. In 1810, various local governments were formed in the country, but Spain regained control.

From Bolívar to el bogotazo, 1819–1948

Simón Bolívar’s victory at Boyacá in August 1819 gave Colombia its independence. Bolívar united Colombia with Venezuela and Ecuador into a unified state (Gran Colombia) and was its president until 1830, but Vice President Francisco de Paula Santander occasionally exercised real power in Colombia. By the time of Bolívar’s death in 1830, Venezuela and Ecuador had formed their own states.

The life of the New Republic was disturbed throughout the 19th century by violent conflicts between liberals and conservatives. The liberals were federalists and anti-clericals, the conservative centralists and church friends. In the 1860s, when the Liberals gained the upper hand, Colombia was organized as a federal state. During Rafael Núñez’s long holding of power (1880–94), the country returned to a centralist state and changed its name from Colombia’s United States to the Republic of Colombia. A new civil war, the most difficult to date, was fought in 1899-1902. It cost an estimated 100,000 lives, but after that began a peaceful period lasting just over 40 years.

Panama became an independent state in Colombia in 1903, after the United States intervened to protect its interests in the planned Panama Canal. Economically, Colombia had experienced a short-lived expansion between 1850 and 1870, based on the export of tobacco and quinine bark, but the real upswing came with the coffee during the last decades of the 19th century. Inner peace and flourishing coffee exports during the first three decades of the 20th century led to a period of economic growth, industrial establishment, infrastructure building and urbanization. Urban middle class, industrial workers, but also more and more urban dwellers with marginal living conditions, formed a new social structure.

The International Depression of 1930 hit Colombia hard, but politically it only meant that the Liberals had to take power from a divided Conservative party. The Liberals won the election again in 1934, and President Alfonso López Pumarejo embarked on a cautious reform effort aimed at improving the conditions of workers and the poor, accelerating industrialization and reducing the power of the Church over the education system. Between 1938 and 1942 a moderate liberal, Eduardo Santos, ruled, and the pace of reform slowed. López was re-elected in 1942 but resigned in 1945 in the face of strong opposition from the military, the conservatives and the moderate parts of his own party. The Liberals were increasingly divided into moderate and reform-friendly phalanges, which is exactly why they lost the 1946 presidential election. Conservative President Ospina Pérez ran a hard-right politics with corporatist elements. In contrast, the reform-friendly phalanx of the Liberal Party became stronger.

Jorge Eliécer Gaitán became the unifying name for the majority of liberals. His anti-oligarchic rhetoric shook the old establishment. The Liberals won big in the 1947 parliamentary elections. Gaitán would probably have become Colombia’s second reform-friendly president if he had not been assassinated on April 9, 1948, in an open street in Bogotá. A few hours later, the city was a mess. Terrible rattles, the so-called el bogotazo, erupted. It was the beginning of a civil war that in Colombia goes by the name la violencia (“the violence”), the bloodiest chapter in the country’s history.

La violencia and Frente Nacional, 1948–86

A ruthless everyone’s war against everyone went on for almost ten years, with hundreds of thousands dead. Conservative forces formed death squads that chased liberals and in the countryside formed communist militias, embryos of today’s FARC guerrillas. During this period the military took power with General Gustavo Rojas Pinilla (1953–57) at the head. To end the violence and remove the military from power, representatives of the Conservative and Liberal Party in 1957 signed a pact called Frente Nacional(‘The National Front’). The agreement meant that the presidential post and government responsibility would rotate between the parties over the next 16 years. The pact was respected and the worst violence disappeared, but at the same time a political power monopoly was created where the other parties were excluded and excluded. The system became a form of institutionalized marginalization of other political forces and violence continued through the emergence of new armed actors in the form of Marxist guerrilla movements (mainly the FARC and the ELN).

The agreement between the Conservatives and Liberals continued in practice even after 1974 under Presidents Alfonso López Michelsen, Julio César Turbay Ayala and Belisario Betancur and was first broken in 1986 by the great election victory of Liberal Virgilio Barco. Barco pledged social reform and, above all, the fight against poverty to create the conditions for political consensus and the elimination of the growing problem of drug cartels.

Drug War, FARC and AUC, 1986–98

But in the 1980s, the power of drug cartels grew due to the new highly lucrative trade in cocaine. Pablo Escobar formed the Medellín cartel and quickly became one of the most powerful people in the country through his ability to buy politicians or by forcing his will by force. In 1984, Escobar tried to negotiate with the government in exchange for the cartel paying off the country’s foreign debt. But under strong pressure from the United States, the government refused to negotiate, which resulted in the Meddellín cartel declaring war on the state. Police, politicians, journalists, lawyers and others who Escobar saw as enemies were murdered and several acts of terrorism were carried out.

In parallel with the fight against the cartels, the government began negotiations with the FARC guerrillas and in 1984 a ceasefire agreement was signed as the start of a peace process. The guerrillas formed a political party, Unión Patriótica (the ‘Patriotic Union’), which ran in local and national elections. However, the party’s members and elected politicians were subjected to a veritable clap-hunting and in a couple of years around 3,000 of the party’s leaders were killed by death patrols dominated by paramilitary groups.

Prior to the 1990 presidential election, the violence culminated and during the campaign four presidential candidates were murdered. In an attempt to put a stop to the spiral of violence and the country’s deep political crisis, a constituent assembly with wide political participation was appointed. Its task was to write a new constitution with extended civil rights. The new constitution was passed in 1991 and several guerrilla movements dropped their weapons, but the two largest, FARC and ELN, interrupted all talks with the government.

The military offensive against the cartels was reinforced and in 1993 Pablo Escobar was killed. The state declared itself a winner in the war on drug power that has terrorized the country since the mid-1980s. But despite the fact that the largest cartels were crushed, drug trafficking did not decrease. The traffic was taken over by smaller and more discreet leagues, and the confrontation with the state that Escobar faced was replaced by a systematic corruption and infiltration of business and political circles, as well as a selective violence against police and prosecutors investigating drug offenses.

During the 1990s, both guerrillas and their opponents, the so-called paramilitary forces, were organized in the umbrella organization AUC (Autodefenses Unidas de Colombia), all the stronger. Both sides were associated with drug cartels and grew both financially and militarily. The rise of the various armed groups took place at the expense of the state’s authority, which in many parts of the country led to varying degrees of anarchy. The conflict became increasingly complicated with many actors and blurred boundaries between allies and enemies. FARC and ELN often fought side by side but sometimes they fought against each other, the paramilitary groups chased the guerrillas and received support from the army while the military officially fought all military groups. Struggles and massacres forced people to flee and the number of internal refugees was between two and three million. The number of political murders was among the highest in the world and also journalists, union leaders and others. became targets.

Government offensive and peace negotiations, since 1998

In an effort to end the conflict, President Andrés Pastrana (born 1954) began negotiations with FARC in 1998. At the same time, the president began an upgrading of the US backed army to attack the guerrillas and drug cartels. After three years of negotiations, the talks and frustration over the missing results of Pastrana’s efforts were interrupted, causing the conservative and hardline Álvaro Uribe (born 1952) to be elected president in 2002. He advocated a military rather than a diplomatic solution to the civil war and stepped up the war against everything FARC. In parallel, Uribe began negotiations with the paramilitary forces gathered in the AUC and the parties signed an agreement that led to tens of thousands of paramilitaries handing in their weapons.

The offensive against the guerrillas pushed back FARC and ELN and the level of violence in the country began to decline. The successes resulted in tremendous support for Uribe and through a constitutional change he could be re-elected for a second term in 2006. Uribe continued the confrontation with guerrillas and for the first time the army managed to kill several people in FARC’s leadership. The military successes occurred while the country experienced strong economic growth and the country’s isolation broke and Colombia became a new favorite country for international investors.

In the 2010 election, Uribe’s party colleague and former Defense Minister Juan Manuel Santos was elected new president. Santos is one of the country’s most powerful families and promised to continue his representative’s policy. Soon, however, he broke with Uribe by, among other things, being open to negotiations with the guerrillas. In October 2012, the talks began formally between the government and the FARC in Oslo, which then continued in Cuba. Santos was re-elected in 2014 and was thus able to continue the negotiations.

In August 2016, the parties finally signed a peace agreement, which was mainly about land reform, drug policy, reparation for the victims of the war, the demobilization of guerrillas and guarantees for its participation in Colombian politics. The agreement was formally signed by President Santos and FARC leader Timochenko (actually Rodrigo Londoño Echeverri, born 1959) on September 26 in the presence of UN Secretary-General Ban Ki Moon.

For the agreement to come into force, a referendum was held on October 2, 2016. With a margin of 55,000 votes, the no-side won by 50.2 percent against 49.8 percent for the yes-side. Almost 38 percent of the country’s voters participated in the referendum. The result was a surprise as all opinion polls predicted a big victory for the yes side. Immediately after the results were presented, both parties expressed their willingness to continue negotiations to find a solution.

A revised peace agreement was finally signed on November 26, 2016 by Santos and FARC’s Timochenko, which was voted through in the November 30 congress. The new agreement contained no major changes but most clarifications on some points, most notably the requirement that guerrillas compensate the victims of the conflict. Former President Alvaro Uribe, who led the no-side in the referendum, was not happy with the changes and continued to oppose the agreement.

In 2016, Santos was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for its efforts to create peace in the country.

FARC was transformed into a political party in 2017 and ran in the 2018 parliamentary elections, but without much success. The right-wing Centro Democrático, led by former President Álvaro Uribe (born 1952) received the most votes in both chambers. However, no party gained a majority in parliament. In the presidential election that year, right-wing candidate Iván Duque won. Duque has promised tax cuts for companies as a way to reduce the informal sector of the economy and investment in better education.