Chile is a country located in South America, bordered by Peru, Bolivia, Argentina and the Pacific Ocean. According to homosociety, it has a population of around 18 million people and an area of 756,096 square kilometers. The capital city is Santiago while other major cities include Valparaiso and Concepcion. The official language of Chile is Spanish but Mapudungun and other indigenous languages are also widely spoken. The currency used in Chile is the Chilean Peso (CLP) which is pegged to the US Dollar at a rate of 1 CLP : 0.0014 USD. Chile has a rich culture with influences from both Spanish-speaking and indigenous cultures, from traditional music such as cueca to unique art forms like Chilean rugs. It also boasts stunning natural landscapes such as Atacama Desert and Patagonia which are home to an abundance of wildlife species.

Colonial period

Before the Spanish colonization, the long coastal strip that is today Chile was sparsely populated. In the 1400s, the Incarct penetrated south of the Andes region, but was unable to establish itself in the areas further south, which were bitterly defended by the Araucan Indians. The Spaniards arrived in 1530, and in 1541 Pedro de Valdivia founded the city of Santiago. Initially, the colony’s interests revolved around gold deposits. However, these were small. Tallow and wheat soon became the most important products of the colony, which was subject to the Viceroy of Lima. Valdivia also failed to defeat the Araucan Indians in their attempt to expand south, and was even killed by these in battle. The Araucans did not give up fighting for their territories, and were largely left in peace until the mid-1800s. Chile played a less significant economic role for Spain than the other colonies. See abbreviationfinder for geography, history, society, politics, and economy of Chile.

The independence

As economic activity was under the effective control of the Viceroy convicted in Lima, the independence movement focused as much on Peru’s dominance as on Spain’s colonial power. The bourgeoisie in Chile evolved to become strongly nationalistic, and from 1810 to 1818 the ties with both Lima and Madrid were considerably weakened. The War of Independence (1817-18) was led by the Irish-Chilean Bernardo O’Higgins, who in 1818 became Chile’s first head of state. However, the conservative landowner class came into conflict with O’Higgins’ attempt to establish widespread international relations, and he was deposed in 1823. Already in 1831, Chile introduced parliamentary governing, and several laws were passed to ensure national control over production and communications. The country experienced a strong capitalist development where mining and industry became important industries. In 1876, Chile produced 62 percent of the world’s copper needs, and the port city of Valparaíso developed into a commercial hub in South America. Both European and American capital interests established themselves in the country, but mining was able to keep Chile under national control. At this time, Chile was also a major exporter of iron ore and coal.

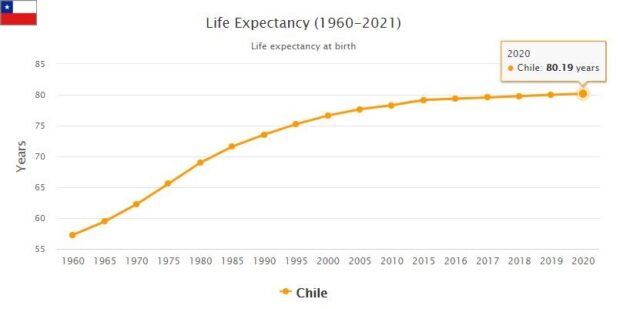

- COUNTRYAAH.COM: Provides latest population data about Chile. Lists by Year from 1950 to 2020. Also includes major cities by population.

Wars and crises

The crisis in the international market in 1873 and the Pacific War 1879–82 led to dramatic fluctuations in the Chilean economy. Copper prices fell drastically, and the United States gained much of the wheat market. The war with Bolivia and Peru led Chile to take control of the disputed nitrate deposits in the Atacama Desert in 1882, and Bolivia lost access to the sea. But the war had further weakened the economy, and it was foreign interests that benefited from the nitrate deposits. President José Balmaceda did not manage to limit the growing foreign control over Chile’s economy. In 1891 he was plunged into a bloody civil war. The mining and industrialization had already in the early 1900s led to almost half of the population living in the cities. Especially in the northern mining areas, which were governed by foreign interests, the workers revolted against the inhumane working conditions. In 1907, more than 2,000 workers were massacred by the Iquique army. In 1912, the first Labor Party was established in Chile, and a massive wave of strikes marked the country during the First World War and subsequent years. At the same time, the country underwent a new crisis as nitrate was synthetically produced in Europe.

The first people front

Chile was in a serious crisis when Liberal Arturo Alessandri was elected President in 1920 by politically freeing the dissatisfied working class. Alessandri was unable to fulfill his promises. The army, which has traditionally been more restrained in Chilean politics than is common in Latin America, intervened in 1924. Three years later, under the military president Ibáñez’s authoritarian rule, North American capital gained a great influence in Chile. The relative upswing in the economy was short-lived. The economic crisis which made its entry in 1929, hit the foundational pillars of the economy. It therefore significantly weakened the bourgeois position of power, and during a hectic period in 1931–32, there was a run-up to the creation of the “Socialist Republic of Chile”. Alessandri resumed the presidency in 1932, but a political front (Frente del Pueblo) consisting of the newly formed Socialist Party, the Communist Party and the Radical Party had established itself in Chilean politics. The national front received considerable support from the working class, which in the 1930s strengthened its position. Then the national industry, which grew to replace the lost import market, became the mainstay of the Chilean economy. The 1938 election was won by the People’s Front, President Pedro Aguirre Cerda came from the radical party. The Communist Party followed the Comintern 1935 recommendation to form alliances with bourgeois parties in the fight against emerging fascism. The political contradictions in Chile therefore polarized during this period. In 1941, cooperation within the People’s Front burst, which in a few years had managed to significantly strengthen the state’s grip on the economy. After World War II, the Communist Party fell victim to the Cold War and was banned in 1948.

The time approx. 1950 approx. 1970

Chile’s relatively radical profile lasted for the 1952 elections, giving the impression that the country stood out in a Latin American context. Political culture could be compared to that prevailing in parts of Europe, and illiteracy was relatively low. Nevertheless, the landowners had a firm grip on the countryside, and like the miners and industrial workers, the land workers lived in very poor conditions. Between 1932 and 1952, the labor movement had developed into a significant factor in Chilean politics. When the former dictator Ibáñez won the election in 1952, there was again increased opposition between the working class and the US-friendly bourgeoisie at a time when the country’s economic problems were precarious. In 1953, the national trade union CUT was established. The Communist Party and the Socialist Party formed ahead of the 1958 general election Front FRAP and placed Salvador Allende as a candidate. With just a win, conservative Jorge Alessandri, son of Arturo Alessandri, won. Another strong candidate in 1958 was Christian Democrat Eduardo Frei, which clearly won the election in 1964. The Frei era was marked by economic reform attempts, obviously in an attempt to win the trust of the working class. However, little of Frei’s ambitious program was carried out, and during his reign, Chile became the country in Latin America that received the most military aid from the United States per capita. The failure of actual reforms was an important factor when Salvador Allende as a candidate for the People’s Unity (Unidad Popular) won the presidential election in 1970.

Allende period

Salvador Allende is often called the first Marxist president to come to power through free elections. The United States immediately expressed concern that Chile would become communist with the consequences it would have for the rest of Latin America. While the new government nationalized the copper mines, banks and parts of the industry, the US responded with technological boycott, denying new credits and suspending all non-military assistance. The powerful truck owner strikes in 1972–73 led to shortages across much of the country, and the daily newspaper El Mercurio ran an intense campaign to cast doubt on the new government. Nationalized US mining companies and the electronics giant, ITT, worked in close contact with the government Nixon to sabotage Allende’s reform program. The result of this polarization was enormous financial problems. Allende was also systematically opposed by the opposition in the National Assembly, which made it virtually impossible to implement the reforms. Military stability depended for a long time on General Carlos Prats, but in June 1973 he was succeeded by General Augusto Pinochet. September 11, 1973, bombers attacked the presidential palace of La Moneda. Allende entrenched himself in the palace to defend his constitutional government with weapons in hand. Allende’s murder was the beginning of a genocide during Pinochet’s protracted terrorist regime.

The military dictatorship

The terror under Pinochet cost more than 3,000 lives, a large proportion in its early years. Thousands of “disappeared” and opposites were arrested, tortured and sent to concentration camps. All political parties were banned, and Pinochet soon made himself a self-appointed leader for a four-man junta. In 1974, he was officially appointed president. Meanwhile, nearly one million Chileans had fled the country.

In 1974, Pinochet created the intelligence agency DINA (later renamed CNI), which became responsible for the repression. Outside Chile, DINA was active. The assassination of Allende’s US ambassador, Orlando Letelier, on Washington’s 1976 open street, led President Carter to later accuse Pinochet of international terrorism. Several other political murders abroad also pointed in the direction of DINA/CNI. Abroad, solidarity actions for Chile became widespread, and the regime was internationally isolated at an early stage.

Economic policy was also drastically changed. Based on Milton Friedman’s economic principles, the labor force was maximally exploited at minimal cost. Foreign companies took over a large part of the former national industry and the service industry. Land reform was abolished. The result was unemployment, inflation and social distress. The debt crisis that hit Chile in the early 1980s was a sign that the economic experiment had failed.

Within the military leadership, it was the hard (los duros) who gradually pushed the more moderate. On the seventh anniversary of the 1980 coup, Pinochet was re-elected president, and a new constitution guaranteed that he could retain power for 1997.

Opposition

As all legal opposition was maneuvered, the number of risky actions against the dictatorship grew. The most well-known armed organization was MIR; in addition, there was a growing public protest against the dictatorship. Although the organized opposition was almost eradicated, in 1983 Chile experienced massive and regular protest demonstrations. The union-dominated Labor National Command (CNT) became the organization that gave Chileans a broad spectrum of social life the belief that change could be achieved. Eventually, the parties stood opener and presented their alliances. The Christian Democrats formed part of the Conservative and Social Democrats in August 1983 the Democratic Alliance (AD). The Communist Party, MIR, parts of the Socialist Party and other radical parties created the month after the Democratic People’s Movement (MDP). Between the AD and the MDP stood the “socialist bloc” (BP). In 1984, Chile experienced several major strikes, supported by the ever-broader opposition. In September 1985, the moderate opposition parties established a “national agreement” (Acuerdo Nacional). Only in May 1986 did joint efforts by virtually all parties to eliminate the 13-year-old mismanagement. But the protests did not reach because Pinochet refused any form of dialogue with the opposition. Following the attempted assault on Pinochet in September 1986, a state of emergency was introduced. Only in May 1986 did joint efforts by virtually all parties to eliminate the 13-year-old mismanagement. But the protests did not reach because Pinochet refused any form of dialogue with the opposition. Following the attempted assault on Pinochet in September 1986, a state of emergency was introduced. Only in May 1986 did joint efforts by virtually all parties to eliminate the 13-year-old mismanagement. But the protests did not reach because Pinochet refused any form of dialogue with the opposition. Following the attempted assault on Pinochet in September 1986, a state of emergency was introduced.

Chile was also a model country for the International Monetary Fund’s prescription on reduced government spending and profitable social investment. A modern bourgeoisie had emerged under the Pinochet regime, but this also meant that the dictatorship became a burden and not just a guarantee of economic and political stability. In 1987, Pinochet allowed several exile politicians to return home to pursue moderate opposition politics in Chile. A referendum was held in 1988 to extend the mandate of Pinochet’s dictatorship until 1996, but this was an embarrassing defeat for the general, who was thus pressured to hold democratic elections. These were held in December 1989 after 16 years of dictatorship.

Democratic opening

A broad opposition alliance of 17 parties, called the Democracies of Democracy (CPD), won the election by over 55 percent of the vote. Christian Democrat Patricio Aylwin became the new president responsible for the transition to democracy in Chile. At the same time, Pinochet secured continued command of the country’s armed forces until 1997. Aylwin was given a cautious opening, although one of the first tasks was to establish a “Commission for Truth and Reconciliation” to investigate human rights violations under the Pinochet dictatorship. The Commission’s report was published in 1991 and documented serious human rights violations and a systematic extermination policy towards the opposition. Unlike Argentina and Uruguay, no settlement was made. To this end, the military was still too influential. The only case to follow up was the 1976 assassination of Chile’s former ambassador to the United States under Allende, Orlando Letelier.

Aylwin’s unity government had confidence in the new bourgeoisie, which contributed to the stability of increased investment. Economic growth not only continued, but increased during the four years Aylwin ruled. Wages rose, while unemployment and inflation fell. There was every reason to be optimistic. Foreign capital also flowed to Chile and contributed to a strengthened economy. The success of the neo-liberal model in Chile made it difficult for the traditional leftist opposition to win. The confirmation that Chile really was among the economically strong countries came in 1994, when the country was invited to join the NAFTA Free Trade Agreement with the US, Canada and Mexico.

Progress had convinced the Chileans. Most of the exile Chileans returned to Chile. CPD reaffirmed its popularity in the 1992 local elections by winning a pure majority. Before the 1993 presidential election, the CPD again stood with a united front, this time with Christian Democrat Eduardo Frei (son of former President Eduardo Frei) as a candidate. The coalition’s victory became even more emphatic than in 1989, and the rejection of Pinochet’s alternative was more clearly affirmed. A heavy legacy for the democratization efforts has been the highly authoritarian constitution drafted by the Pinochet regime in 1980. Frei failed to gain a sufficient majority to achieve constitutional amendments during his first year of government.

Settle with the past

A legal persecution of Augusto Pinochet was eventually initiated – outside the country. In 1998, he was arrested and placed under house arrest during a visit to the United Kingdom, the same year he resigned as commander of the Armed Forces and was granted Senator statusfor life. The reason for the arrest was an extradition claim from Spain, based on charges of murder and torture of Spanish nationals during the dictatorship. Chilean society was divided in its attitude to the arrest; as it was in relation to Pinochet whatsoever – a decade after the dictator’s departure. That both hatred and sympathy became evident was evident in the media and street scene when he returned to Chile in March 2000, after the British authorities declared him unfit for extradition and trial. Shortly thereafter, the Chilean Supreme Court revoked the immunity from prosecution that came with the office of senator. abduction and killing of 75 political opponents in the years 1973–90. Pinochet consistently denied all guilt. It all culminated in 2001, when the Appeal Court in Santiago, with 2 to 1 votes, ruled that the trial should be postponed until the state of health of the then 85-year-old and physically and mentally severely impaired Pinochet had improved. When he announced his resignation in 2002 as a life-time senator as well, it triggered such strong feelings in the National Assembly that the police had to enter the hall to muffle the crowd. The following years lawsuits were initiated and interrupted several times, until Augusto Pinochet died in December 2006. Then the Chilean community’s ambiguous attitude towards its former dictator came to light again with the government’s refusal to state burial and official mourning – but yes to military honors.

In 2003, 30 years after the military coup, the time was ripe for a public rehabilitation of the assassinated President Salvador Allende, and a recovery for relatives of the more than 3,000 killed and “disappeared” during the dictatorship. Both a collaboration with Argentina and an amnesty for the military that will explain themselves were initiated to clarify the numerous cases, and prosecution against hundreds of officers was raised. An almost 15-year-old taboo was finally broken.

A socialist at the helm

The 1999/2000 presidential election was won by the moderate Socialist Ricardo Lagos Escobar of the Democratic Party (PPD, Partido por la Democracia), who he helped to found. In the second round, he won, with 51.3 percent of the vote, over right-hander Joaquín Lavín. Lagos was a member of Salvador Allende’s government before the military coup in 1973. In the 1980s, he was imprisoned for leading an opposition group that sought to overthrow the Pinochet regime. He also served as Minister of State in Eduardo Frei’s government in the 1990s. The parties behind the president’s center/left coalition declined somewhat in the 2001 general elections, and Lavin’s conservative party stood out most, compared to the 1997 elections. However, the highest percentage increase was achieved by the UDI, Unión Demócrata Independiente on the outer right wing – which is the political base for the Pinochet sympathizers.

The presidential election in 2005/06 was won by socialist and pediatrician Michelle Bachelet. She received 53.5 percent of the vote in the second round of elections on January 15, 2006, thus becoming the first elected female president of South America. In conservative Catholic Chile, a change of time also warned that a declared agnostic and single mother with three children from as many previous relationships reached the top of politics. Likewise, her past as a torture victim in the Pinochet era was given weight to the electorate. The electoral victory triggered a popular party in Chilean cities. The new government received a 50 percent female share, and among the first, radical changes to the law was the legalization of divorce, to protests from the Catholic Church.

Economic policy

Throughout the 1990s, Chile was the South American country with the strongest economy and strongest growth, and recovered relatively quickly after the turmoil in Russia’s economy and the Asian crisis; shakes that contributed to a deep and protracted crisis in Brazil and Argentina. Privatization of state industry is a political main line that has been continued under changing governments. However, a major challenge, besides combating poverty, has been to make the economy less dominated by copper production. After a strong investment in seafood, this industry accounted for 12 percent of export revenue at the beginning of the new centenary. In the first part of Michelle Bachelet’s reign, Chile further consolidated its position as Latin America’s strongest economy, with annual growth of around 6 percent, foreign debt freedom and ever-declining unemployment. The large proportion of poor people generally got noticeably better, even though the gap between poor and rich continues to widen. It was the result of a deliberate foreign policy when Chile signed free trade agreements with The EU – the most comprehensive agreement a non-member has reached – and with EFTA, the US and South Korea. Together with neighboring countries, Chile wants to play an important role in the pursuit of a more just world trade.

Chile after 2010

Presidential elections around the turn of the year 2009/2010 were won by center/right candidate Sebastián Piñera, who obtained 52 percent of the votes in the second round, against center/leftist Eduardo Frei (president 1994-2000). Piñera is a former economics professor, owns interests in a number of large companies and is featured in Forbes magazine’s list of the world’s richest. The left-wing hegemony since the fall of the Pinochet regime in 1990 could thus be said to be broken, and the left parties were characterized by wear and tear. But a prevailing impression in the election was that the market-oriented center course that has been conducted in recent years – also under Social Democrat Michelle Bachelets governance – would be continued. With the Obama-inspired slogan “change,” Piñera aimed for more efficiency in state and private enterprise, tax cuts and other stimulus measures to bring annual economic growth back to 6 percent, which was the level before the 2008 financial crisis, brought the first recession to ten year. The Chilean Constitution does not allow a president to serve two consecutive terms, and Bachelet took over the presidential post again in 2014.