Austria is a small country located in Central Europe bordered by Germany, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Slovenia, Italy and Switzerland. According to homosociety, it has a population of over 8.8 million people and an area of 83,871 square kilometers. The official language is German while English and French are also widely spoken. The currency used in Austria is the Euro (EUR). The capital city of Austria is Vienna which has a population of over 1.8 million people. The climate in Austria varies from temperate to continental with cold winters and warm summers. Agriculture plays an important role in the economy with grains, vegetables, fruits being some of the main crops grown. Austria also has rich mineral resources such as copper, iron ore and lead-zinc ores. Despite its natural resources however it remains one of the most developed countries in Europe due to its strong economy and low unemployment rate.

Austria’s history is characterized by the country being on the border between eastern and western Europe. The land was created as a field county by Karl the Great in the late 700s. In the 13th century, the Habsburg family came to power. Austria eventually came to encompass large parts of Central Europe, becoming a European great power.

In 1804, Austria became an empire, from 1867, with Hungary as an equal part of the double monarchy of Austria-Hungary. After the defeat in World War I, the double monarchy was disbanded and Austria became a republic. Prior to World War II, Austria was annexed by Germany in the so-called Anschluss. After the war, Austria became neutral. In 1995, the country joined the EU.

Medieval

The origin of Austria is the “east land” or the land county – Marchia Austria – which Karl the Great created in the late 700s to defend Bavaria and France’s eastern border against the Turkish avars. See abbreviationfinder for geography, history, society, politics, and economy of Austria. For a short time, the Madjans were lords of the country, but in 955 the land county was resurrected, and from 976 the Babenberg family reigned there.

In 1156 Austria became its own duchy during the German-Roman Empire, and in 1192 the dukes became gentlemen in Styria. In 1246, the Babenbergs died out, and King Ottokar 2 of Bohemia laid down the duchy in 1251. In 1260 he took Styria and in 1269 Carinthia and Krain, but in 1276 had to give it all to Rudolf of Habsburg.

Rudolf in 1282 transferred Austria, Styria and Krain to his son Albrecht, thus laying the groundwork for the Habsburgs. The family expanded in 1363 its area with Tyrol. From the middle of the 1400s, the title of Archduke was officially related, and from 1438 the dignity of the German King and Roman Emperor was permanently linked to the Habsburg Archduke of Austria, which thus managed to consolidate a strong firepower. But their attempts to conquer Switzerland had failed in the 1300s.

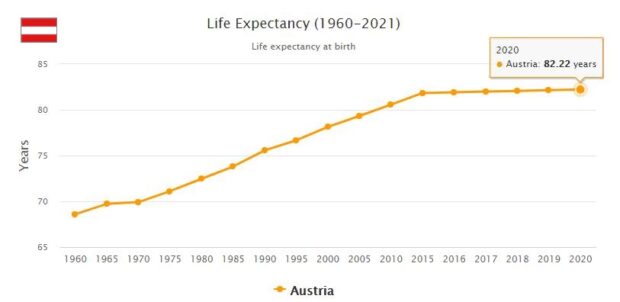

- COUNTRYAAH.COM: Provides latest population data about Austria. Lists by Year from 1950 to 2020. Also includes major cities by population.

Early modern times

In 1493, Emperor Maximilian 1 gathered all the Austrian heirs under his rule, and by the division of Germany in 1512 he made them a separate circle. Under him and his grandson Karl 5 (Emperor 1519–1556), the Habsburg Empire reached its peak, but when Karl dropped the crown, the lineage was divided into two lines: the Spanish and the Austrian. The Austrian line retained the imperial dignity, which passed to Charles’s brother Ferdinand 1. All in 1526, by marriage and election, this had won both the Bohemian and the Hungarian crown. This led to a lasting unification of the Austrian, Bohemian and Hungarian countries, although most of Hungary remained under the Turks until 1699.

Indeed, during the first hundred years of the new Habsburg kingdom, the center of gravity lay in the Slavic countries, and Prague was the usual seat of government under Emperor Rudolf 2 (1583–1612).

As king of Bohemia, the emperor was at the same time the German ruler, but the attempts to strengthen the Habsburg emperor power in Germany did not go ahead, and after 1648 the emperor had no real power there. In his own inheritance, however, in the 17th and 18th centuries, it developed into an actual monarchy. It was natural for the Habsburgs to weld the old individual states and the many different peoples who lived there, together into a centralized unitary state, and this dynastic policy was linked to the issue of religion. The Czech lands had been in a unique position since the 15th century with the Hussites, and in the following century the Protestant doctrine won over Catholicism in all three parts of the kingdom, especially among the nobility and the citizens.

Consequently, the effort for religious freedom went hand in hand with the Standing Assembly’s attempt to extend its power to the prince’s house. The prince’s house, for its part, fought for unanimous power and for the Catholic Church. Ferdinand 2’s victory over the Czechs in 1620 also became a victory for the monarchy over the old stender government, and a victory for Catholicism over Protestantism. The Bohemian countries became more closely associated with Austria than the Hungarians, and from 1526 the three groups of countries developed steadily and two into two: the Austro-Czech and the Hungarians. The former got joint administration, common courts and eventually also common law, and the official language became German, while three-quarters of the Czech nobility’s land passed to German hands.

This embarrassment was deliberately promoted by Empress Maria Teresia and Joseph II in the 18th century to create a national and linguistic unity. At the same time it increased the difference between the Austro-Czech and the Hungarian part of the empire, because Joseph’s reforms were to a much lesser extent implemented in Hungary. Also economically, inequality increased from the end of the 18th century due to the development of a substantial bohemian industry. From a foreign point of view, it was from the first moment the historical role of the Habsburg kingdom in Europe to form a bulwark against the Turks (the Ottoman Empire), which twice reached as far as Vienna. With the peace of Sremski Karlovci (Karlowitz) in 1699, the Turkish danger was finally over, and Austria was given most of Hungary and Transilvania (Siebenbürgen). In the years 1699-1737 the rest of Hungary was also placed under the Habsburgs.

From the end of the Middle Ages to the mid-1700s, France was Austria’s main opponent in the power struggle for supremacy in Europe. This was true during both the Thirty Years War in 1618–1648, the Spanish Succession War in 1701–1713, the Polish Succession War in 1733–1735, the Austrian Succession War in 1740–1748 (after the Habsburgs line of men had died out with Charles 6 and he was followed by daughter Maria Teresia) and finally in the Prussian Seven Year War in 1756-1763.

In these wars, Austria lost Lausitz (1635) and most of Silesia (1742), but the losses were more than offset by new land victories: After the Spanish succession war, Austria gained the Spanish Netherlands (Belgium) and large areas in Italy. At Poland’s first division in 1772, Austria gained Lvov and East Galicia (82,000 square kilometers), and also Bukovina in 1777. At Poland’s third division in 1795, Austria got West Galicia with Kraków(47,000 square miles). Following the Alliance during the Prussian Seven Years’ War, Austria and France again became major opponents during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars, leading to large Austrian land divisions, especially during the Vienna Peace in 1809.

Maria Teresia carried out several important reforms in the spirit of the Enlightenment: torture by interrogation was abolished, the noble privileged position curtailed and the peasants’ legal position towards the landlords was regulated by law. But the quality of life was not abrogated. From 1765 her eldest son, Joseph, was 2, included. He continued his mother’s reform program. The quality of life was abolished the year after her death in 1781, and the Catholic Church’s position of power was severely curtailed. Joseph 2 did much to improve the school system and decided that German should be the main language. This provoked reluctance among the Hungarians and the Czechs, and also other of his reforms created unrest. Joseph abolished many of them in his last years of life, but did not restore the quality of life.

The Empire of Austria, 1804-1867

Joseph was succeeded in 1790 by his brother, Leopold 2, who, against his will, was drawn into the coalition against France, where Sister Maria Antoinette sat in jail awaiting his verdict. However, Leopold died as early as 1792, and it was his son Frans 2 who suffered many defeats in the wars with Napoleon. In 1804 Franz took the title of Archduke of Austria, and in 1806 the German-Roman Empire was dissolved.

In 1810, his daughter, Maria Louise, married Napoleon, and their son Napoleon 2, the “King of Rome, ” was born the following year. At the Vienna Congress in 1815, Austrian Minister Metternich succeeded in regaining many of the lost territories (but not Belgium, which was united with Holland to the Kingdom of the Netherlands).

Under Metternich’s leadership, Austria played a leading role in the “Holy Alliance”. But he was hated by the emerging bourgeoisie for his reactionary attitude. The February revolution in Paris in 1848 led to the rise of the bourgeoisie and workers in Vienna, and to national riots in Italy and Hungary. Metternich fled, and the emperor had to issue a liberal constitution with universal suffrage. The quality of life was completely abolished and liberal reforms introduced.

But the reaction could play to the contradictions between the Madjars, the Slavs and the German liberals. An imperial army conquered Vienna, and Hungary was broken with Russian aid. In the 1850s, all opposition was held down with hard hand and a bureaucratic centralization carried out according to French pattern.

Austria in the double monarchy, 1867-1918

Austria’s position of power rested on the alliance with Russia, but this was broken during the Crimean War in 1853-1856. Austria, therefore, stood alone in the war against Sardinia and France in 1859, and lost dominion in Italy (loss of Lombardy). At the same time, Austria’s leadership in the German Confederation was threatened by Prussia. The rivalry with Prussia in 1866 led to war. Austria was defeated and placed outside the development that led to a new German national organization, and in addition Venice was lost to Italy.

The following year, a settlement was reached with Hungary, which was recognized as an equal national element in the double-monarchy of Austria-Hungary. A real union was established with, among other things, the common foreign and military system. Franz Joseph became Emperor of Austria and King of Hungary.

Austria was primarily an agricultural country, but an industry developed, including in Vienna and Bohemia. In each of the 17 countries in Austria was the country days next to the main board (Emperor and riksråd with two chambers). In 1907, ordinary voting rights for men were introduced to the Second Chamber. After 1880, modern mass parties emerged. The German bourgeoisie joined the “German nationals”, while the petty bourgeoisie and later the peasants advocated for the Christian-social party led by Karl Lueger. As in Germany, a social democratic mass party emerged on Marxist grounds under Victor Adler.

However, parliamentary life was ruined by the country’s fundamental problem, the national issue, and the country was governed by emergency regulations. The two national units were composed of different nationalities with the Germans in Austria and the Madjars in Hungary as dominant.

Towards the end of the century, the fragmentation trends became stronger in the country. The non-German nationalities – Czechs, Poles, Roots, Croats and Slovenes – opposed the political leadership position of the German-speaking population (similar to the many minorities in Hungary who were in opposition to the Madjars), and demanded autonomous rule, independent state formation or association with neighboring nation states. Austria’s relations with the independent Slavic Kingdom of Serbia and its protector Russia deteriorated when Austria in 1908 annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina.

World war one

The contradictions between Austria and Serbia, which wanted to incorporate the parts of the double monarchy where southern Slavs lived, immediately led to the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. Crown Prince Franz Ferdinand was murdered by Serbian nationalists on June 28, 1941, during an attack known as “the shootings. in Sarajevo ». Austria felt that Slavic nationalism was a threat to the existence of the kingdom, and therefore fought hard against hard against Serbia.

The war in the east against the Russians led to preliminary losses (Galicia) and gains (Poland). Despite that Austria offered to refrain Trentino and do Trieste to free state, declaring Italy the war in 1915, and Romania, which wanted Transylvania, followed in 1916. At the German aid was the Romanians turned, and the front against Italy stabilized.

The defeat and distress fueled a growing opposition. In 1916, Victor Adler’s son Fritz Adler fired the prime minister, Count Karl von Stürgkh. The same year, Emperor Franz Joseph, who had ruled since 1848, died. He was succeeded by his great-nephew Karl 1. Circuits in the imperial family had peacekeepers out with the allies, who did not really have Austria-Hungary’s resolution as a war target. Among the national minority, the Czechs were particularly active. In Russia, they formed a Czech legion, and in Paris a “Czechoslovak National Council” was formed under the leadership of Tomáš Masaryk.

Foreign Policy

Austria was instrumental in the formation of EFTA in 1959 and became associated with the EC through an agreement in 1973. Events in Eastern Europe at the end of the 1980s, and in particular Germany’s collection, also changed Austria’s state law position. The country renounced several of its obligations from 1955, and in the summer of 1989, Austria applied for EU membership. The country negotiated with Sweden, Finland and Norway, and in the June 1994 referendum, 66.4 percent of voters voted for membership. On 1 January 1995 Austria became a member of the EU, and the country signed the Schengen Agreement in 1998.