Albania is a country located on the Balkan peninsula in Southeast Europe. It is bordered by Montenegro, Kosovo, North Macedonia, and Greece. According to homosociety, it has a population of approximately 2.9 million people and an area of 28,748 square kilometers. The official language is Albanian and the currency is the Lek (ALL). The capital city of Albania is Tirana which has a population of over 800,000 people. The climate in Albania varies from subtropical in the south to continental in the north with hot summers and cold winters. Agriculture plays an important role in the economy with olives being one of the main crops grown. Albania also has rich mineral resources such as chromite, copper and iron ore. Despite its natural resources however it remains one of the poorest countries in Europe.

Prehistory

According to European conditions, the prehistory of Albania is still (1996) incompletely known. The oldest finds are from the Middle Paleolithic (about 300,000-40,000 years ago), but the lack of older finds is probably apparent. A large part of the investigated settlements dates back to the entrance of the Neolithic (c. 7000 BC) cave dwellings. Albania’s oldest neolithic belongs to the western Mediterranean so-called impression ocardium group, so named for its characteristic ceramic decor. During the Neolithic, a cultural equalization took place in relation to the central Balkans and northern Greece, and during the copper age (about 4000-3000 BC) several settlements were built that can be followed into the Bronze Age.

Only a few graves from the older Bronze Age have been examined; By contrast, the younger Bronze Age is richly represented through both settlement finds and tomb finds, which bear similarities both to northern areas and to northern Greece. Also from the older Iron Age (about 1000-500 BC) are many finds; During this period fortified settlements were built, many of which had very strong walls. From the 7th century BC the Greek influence greatly increased, and the following century Greek colonies were founded on the coast (compare Epidamnos). For further developments in Albania during antiquity, see Illycer and Illyricum. See abbreviationfinder for geography, history, society, politics, and economy of Albania.

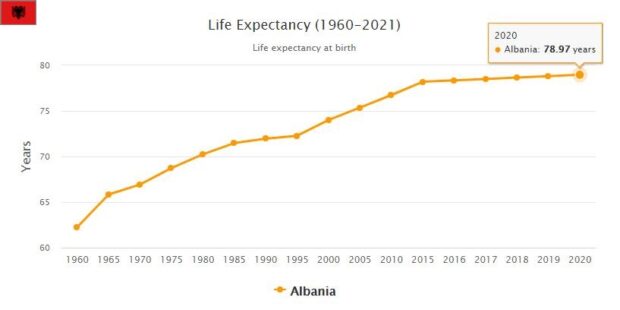

- COUNTRYAAH.COM: Provides latest population data about Albania. Lists by Year from 1950 to 2020. Also includes major cities by population.

History

Albania has been at the intersection of various major powers, languages and religions. Greeks and Romans, Goths and Byzantines, Serbs and Bulgarians, Sicilians and Venetians, Turks, Italians and Germans have all embraced the area for short or longer periods. During Roman times it was counted as part of the provinces of Illyria and Epirus. When the Roman Empire was divided in 395, it came to obey the Austrian Empire. The mountain tribes, however, largely retained their independence. In the 1100s, the first Albanian state was formed, but it became short-lived. When the Turks tried to invade the area, the national hero Georg Kastriota, better known by the name Skanderbeg (by the Turkish Iskanderbeg) succeeded = Prince Alexander), one of the different tribes in a common resistance and for a quarter of a century the Turks hold the bar. After Skanderbeg’s death in 1468, however, the Turks were able to incorporate Albania into their realm, and the country, despite several rebellions, remained under Turkish supremacy until the early 1900s.

In the mid-19th century, a national movement arose, which fought for the right to use the Albanian language but eventually grew into an increasingly revolutionary, national liberation organization. On November 28, 1912, in the town of Vlorë, a National Assembly was convened, which proclaimed Albania an independent state. However, the states of the Balkans (ie Serbia, Bulgaria, Greece and Montenegro), which in the autumn of 1912 had attacked and succeeded in defeating the Turks in the fall of 1912, had planned to divide Albania among themselves. Only after the end of the Second Balkan War in 1913 could Albania’s borders be established and independence recognized. Albanians hope that all areas that at that time had Albanian majority population would be included in the new state, such as the province of Kosovo, however, came to shame. Albania’s independence would be guaranteed by an international control commission. This put a Prussian, the Prince of Wied, in charge of the country. A popular revolt forced him to leave the country after only six months.

Although Albania was neutral, it was occupied in various stages during the First World War, and after the end of the war, the victorious powers discussed how the country should be divided. Italy had the greatest influence, which for a few years held troops in the country. However, the Albanians rebelled in 1920; a national government was formed in Tirana, which became the capital, and the pro-Italian government in the city of Durrës was overthrown. After years of internal strife, Ahmed Bey Zogu, a clan chief from the north, was able to take power in 1925 with, among other things, Yugoslavian assistance. He ruled dictatorially and in 1928 made himself proclaimed to King Zog I. During him, Albania became increasingly dependent on fascist Italy. When Albania was occupied by Mussolini’s troops in the spring of 1939, the country was in fact an Italian colony. Zog fled abroad with the Treasury.

In September 1943, Italy capitulated to the Allies. The Italian occupation troops were replaced with German, but by then a partisan army had already begun the fight against the invaders. The partisans consisted of various resistance groups but were led by Enver Hoxha, leader of the 1941-founded Albanian Communist Party. By November 29, 1944, the country had liberated itself from foreign troops by its own power, but by October Hoxha had formed a provisional government. On March 14, 1946, the country was proclaimed to the People’s Republic of Albania and a constitution was adopted.

After the war, Albania had become very dependent on Titos Yugoslavia and was about to merge with Kosovo into the seventh sub-republic of Yugoslavia. However, when Stalin broke with Tito in 1948, Hoxha also broke with Tito. Albania, unlike other communist countries, came to consistently adhere to the Stalinist interpretation of Marxism-Leninism. The Yugoslav influence was transformed into a sharp Albanian-Yugoslav enmity, and although relations gradually improved, the issue of Albanians in Kosovo remained as a matter of war.

Albania became a member of COMECON in 1949 in 1955 in the Warsaw Pact (as well as in the UN) and received extensive Soviet assistance against the Soviet Union obtaining a naval base in Dürres. When, after Stalin’s death, the Soviet Union approached Yugoslavia, Albania wanted to do the same. At the same time, it was demanded that Albania should focus on growing agricultural products to other eastern states and buy industrial products from them. Due to the requirements, good relations between the countries deteriorated. When Albania captured China’s party in the Sino-Soviet ideological conflict, the Soviet Union broke relations with Albania in 1961, leaving the base in Dürres. Albania in turn left COMECON in 1962. In 1968, after the Soviet march in Czechoslovakia, Albania also resigned from the Warsaw Pact. Soviet aid was exchanged for Chinese, but when China entered into relations with the United States in the 1970s and sought improved relations with Yugoslavia, Albania also distanced itself from China. When Chinese aid ceased in 1978, Albania’s isolation was almost complete. When Enver Hoxha died in 1985, no foreign delegations were allowed to attend the funeral. Hoxha had been sitting in power for longer than any other European leader. He had characterized the whole of the history of modern Albania, and around him a great cult of personality had arisen. The former party leader remained in power through skill, but also through great ruthlessness. Not least, Hoxha relied on the military and the dreaded security police, Sigurimi. Dissent thinking was executed, imprisoned, interned in labor camps or banished within the country, and political competitors were eliminated.

Albania was at Hoxha’s death Europe’s poorest country. Several years of misery had exacerbated the already difficult economic situation created by many years of isolation and strong population growth. Hoxha’s successor, Ramiz Alia, realized that Albania needed external help and began to introduce cautious reforms. However, it was not a matter of radical changes, and when the improvements failed, dissatisfaction spread among the population. Despite the isolation, many were also aware of the upheavals that were taking place in the rest of Eastern Europe. Demands for democratization of Albania also increased, while more and more Albanians tried to leave the country, most on overcrowded old ships to Italy. After extensive student demonstrations in December 1990 in the capital Tirana, the all-ruling Albanian Labor Party agreed that other political parties should also be formed. Nevertheless, the flow of refugees from Albania continued.

The first free parliamentary elections took place on March 31, 1991. They became a great success for the Labor Party, which still had strong support in the countryside. The largest opposition party, the Democratic Party, formed by intellectuals and students, had great success in the cities. A government was formed under Fatos Nano, and Ramiz Alia was appointed president. However, widespread protests against the poor economic conditions in the country and a general strike led the new government to resign in June in favor of a coalition government, which included both the Labor Party and the Democratic Party. At the same time, the Labor Party changed its name to the Socialist Party. In the recent election held in March 1992, opposition parties won big and the Democratic Party’s Sali Berisha replaced Ramiz Alia as president. A campaign was launched to eradicate communism. Among other things, a number of leading communists were brought to trial, including Alia, Hoxha’s widow Nexhmije and Fatos Nano. The trial against Nano was heavily criticized by Amnesty International, and the Socialist Party talked about political punishment. A form of arbitrary occupational ban was also introduced against persons who held important posts during the communist era.

In May 1996, parliamentary elections would be held again. However, the Socialist Party had had great success in the local elections, and for fear of losing government power, the Democratic Party turned to obvious electoral fraud, which was also confirmed by international observers. Nevertheless, the party formed a new government, now together with some smaller parties. However, criticism increased against Berisha, who began to rule the country more and more simply and gathered more power in her own hands by getting rid of her competitors and taking full control of the mass media. He used the same methods as during the Hoxha era. Among other things, he let the security police, SHIK, harass political opponents in a manner reminiscent of Hoxha’s dreaded Sigurimi.

The dissatisfaction with the regime exploded on New Year 1997, when the so-called pyramid games collapsed. These were a type of investment fund that operated according to the chain letter principle. Most Albanians had been attracted to invest all their assets in these funds, which could initially pay off big profits. However, the money soon ran out, and many Albanians then lost everything. During the spring of 1997, violent unrest spread throughout Albania, but the worst hit in the southern part. Arms and shops were looted, and sheer lawlessness prevailed in many places. Finally, the government was forced to ask the outside world for help to restore order, and soldiers, mainly from Albania’s neighboring countries, intervened in the so-called Operation Alba. Berisha was forced to announce new elections. Not surprisingly, the Socialist Party won the election held on June 29. A month later, the party’s secretary general was appointed, Rexhep Mejdani, new president. New Prime Minister became Fatos Nano, who was released from prison during the unrest.

The new government’s primary task was to collect the weapons that were still in circulation and regain control of the entire country, and to gain momentum for the economy. The first two were resolved reasonably, while the economy was hit hard by the nearly half a million refugee flow from the Kosovo war in 1998-99. However, most refugees could return and together with The IMF initiated an ambitious economic reform program. Reforms were also initiated in a number of other areas, all with the aim of preparing Albania for membership in Western organizations such as the EU and NATO.

In the 2001 election, the Socialist Party gained its own majority, but the party was characterized by major internal problems. Among other things, Fatos Nano, from the “old guard”, was deposed several times but had returned as party leader to finally resign after the 2005 election, won by the Democratic Party under Sali Berisha. Nano was succeeded as Socialist Party leader by Tirana Mayor Edi Rama. Nano was also not supported by his party in several attempts to become president; instead, in 2002, the compromise candidate Alfred Moisiu was elected head of state, which in 2007 was succeeded, but only after several votes in parliament, by the Democratic Party’s Bamir Topi. The parliamentary elections in the summer of 2009 led to a very tight victory for the Democratic Party, whose leader Sali Berisha could thus continue as prime minister. The scarce margin, however, led to pronounced suspicions of electoral fraud and boycotts by the Socialists. Bad elections and clean cheating have occurred in Albanian elections since 1990, but some improvements have since been incremental.

In the run-up to the 2013 parliamentary elections, the political contradictions hardened. The election result meant that the Socialist Party could regain power with party leader Edi Rama as prime minister.

The party formed government together with the smaller party Socialist Movement for Integration (LSI), which was formed as a breakout party from the Socialist Party and formed a previous coalition government with the Democratic Party but supported the Socialist Party in the 2013 election. LSI’s founder Ilir Meta was elected Albania president in 2017.

Even before the June 2017 parliamentary elections, the political situation was troubled. This was reflected in the opposition’s boycott of parliamentary work. It called for an independent government, including the opposition, to be established, which they thought was the only way to make fair elections. Through mediation by the US and the EU, the opposition was partially heard for their demands and the elections could, somewhat delayed, be carried out without major problems.

The Socialist Party and Edi Rama gained continued confidence and, through a convincing victory, could form government on their own.

Although the economy has been growing all the time, albeit not as rapidly in recent years, Albania was still one of Europe’s poorest countries in the mid-2010s. The country is run by a lack of infrastructure and a large informal sector.

Although much remained to be done, economic and democratic reforms had nevertheless been so successful that in April 2009, the country, along with Croatia, was accepted as a full member of NATO.

In June 2014, Albania was accepted as a candidate country for the EU and in November 2016, the EU Commission recommended that membership negotiations be opened with Albania as soon as the legal reform adopted that year also came into force.