Honduras is a country located in Central America, bordered by Guatemala, El Salvador, and Nicaragua. According to homosociety, it has a population of around 9 million people and an area of 112,492 square kilometers. The capital city is Tegucigalpa while other major cities include San Pedro Sula and La Ceiba. The official language is Spanish but many other languages such as Garífuna and Miskito are also widely spoken. The currency used in Honduras is the Honduran Lempira (HNL) which is pegged to the US Dollar at a rate of 1 HNL: 0.037 USD. Honduras has a rich culture with influences from both Mayan and Spanish cultures, from traditional music such as punta to unique art forms like Lenca pottery. It also boasts stunning natural landscapes such as Pico Bonito National Park and Celaque National Park which are home to an abundance of wildlife species.

The western part of Honduras was part of the Mayan kingdom that had been destroyed before Kristoffer Columbus arrived on the coast in 1502. One of the best-preserved Mayans, Copán, is in Honduras. The Spaniards found little interest and the indigenous people exercised great resistance until the Lenca chief Lempira was killed and his 30,000 warriors surrendered in 1537, the same year that Comayagua became the provincial capital.

Central America’s first university was founded here in 1632. Mining was commissioned from the late 16th century in the area around the present capital Tegucigalpa. The long coast towards the Caribbean was partly under British control throughout most of the 17th and 18th centuries.

The British had bases off the coast which were the link between Belize and their sphere of influence which lay under the Miskitu kingdom and stretched along the coast to Nicaragua and Costa Rica. The people of the coast are largely descendants of African slaves.

Independence

On September 15, 1821, Honduras along with the other provinces of Central America became independent from Spain. See abbreviationfinder for geography, history, society, politics, and economy of Honduras. One of the foremost champions of a united Central America was Honduran General Francisco Morazán; he suffered defeat in 1838 when the union was dissolved and the five republics formed. The instability in Honduras was noticeable. Between 1821 and 1876, a total of 85 presidents ruled, of which General José María Medina eleven times.

One of the reasons why a strong state power did not emerge in Honduras was that the landlord class was weak. The country also failed to develop a strong coffee economy like Guatemala and El Salvador. Corruption was so widespread that at an early stage the country struggled with large foreign debt. Instead, foreign companies became dominant in Honduras.

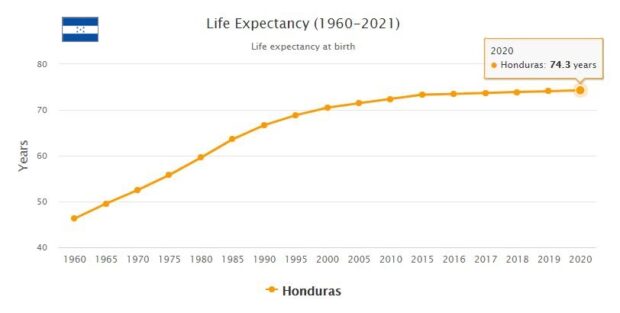

- COUNTRYAAH.COM: Provides latest population data about Honduras. Lists by Year from 1950 to 2020. Also includes major cities by population.

The term “banana republic” was first used about Honduras, as international companies have had a greater influence over the country’s governing powers than the inhabitants themselves. North American banana companies have dominated both the economy and politics of the country since the late 1800s.

Railway companies

US banana companies received exceptionally favorable licenses for banana plantations along the Caribbean coast in the 1890s, which laid the foundation for the large-scale Standard Fruit group. In 1913, banana production accounted for 66% of total exports, and banana companies took care of much of the infrastructure in the country. Ever since President Marco Aurelio Soto was overthrown in 1883, the country had been characterized by civil wars, and the banana companies were trying to help one or the other party in the conflicts to achieve even better conditions. Traditionally, Standard Fruit supported the Liberal Party, while United Fruit supported the National Party.

As a result of the worldwide crisis in 1929, unemployment and unrest increased due to the strong dependence on the banana companies. As in the other Central American countries, this led to military dictatorship, where General Tiburcio Carías Andino ruled hard-fought from 1932 to 1948. The unions became militant during the same period, and were met with violent repression by the regime.

In 1954, Honduras experienced such extensive strikes that banana production was completely paralyzed. The unions were strong enough to be pushed through reforms that in 1959 led to a separate workers’ law. Since 1963, when General Oswaldo López Arellano took power, the army has been the real power in the country. This created better stability for the foreign banana companies.

Football war

López was re-elected in 1965 as a candidate for the national party. His modernization efforts were strongly linked to the creation of the Central American Common Market (CACM) and cautious land reform. The industry developed, but to a lesser extent than in neighboring countries. It was the foreign companies that drew the greatest benefits. Unemployment increased and did not improve as around 300,000 Salvadoran people came to the country to find work. Land reform was extremely slow, and rural conditions were miserable.

The so-called “football war” in 1969 against El Salvador was due to the dissatisfaction with the imbalance in the common market and the growing confrontations around land rights, in which many Salvadoran immigrants were involved. Salvadoran military forces entered Honduras to defend their countrymen, and relations between the two countries have been conflicting ever since. López Arellano regained power in 1972, but had to step down in 1975 following a corruption scandal with the banana companies trying to resist taxation. Instead, Honduras experienced a military-populist phase under Juan Alberto Melgar Castro, which lasted until 1978 when Policarpo Paz García seized power through the country’s 138th military coup.

American base

The Sandinist revolution in neighboring Nicaragua quickly brought Honduras to the United States. The country borders all three Central American countries where revolutionary movements were very active, but in Honduras no guerrillas of a notable kind had developed. The election of Ronald Reagan as President of the United States in 1980 led to a significant increase in US economic and military assistance.

Honduras also has Central America’s largest air force. Although Liberal Roberto Suazo Córdova won the election in the fall of 1981, it was General Gustavo Álvarez Martínez who had the real power. Honduras became the base of operations for Nicaraguan counter-revolutionaries (contras) and the almost permanent US military maneuvers served as part of the secret war against Nicaragua.

The Central American Peace Plan

The reign of José Azcona Hoyo (1986-90) became crucial for Central America. In cooperation with the other presidents of the region, the Central American Peace Plan was launched in 1987, where Azcona pledged that counter-revolutionary activities against Nicaragua would no longer be carried out from Honduran territory.

The government of Rafael Callejas of the Conservative National Party (PN), who was elected for the period 1990-94, placed the military under a newly created Department of Defense. Callejas paved the way for a modernization policy that assumed dramatic dimensions when already weak social programs, labor rights and wage policies were sacrificed in favor of privatization, austerity and tax benefits for the privileged.

A new law on agricultural modernization from 1992 led to investments in large estates and plantations, and many small farmers and landless people gave up and moved to the cities to seek employment in an already tight labor market. Callejas received a lot of criticism, and it got worse towards the end of his reign, as several cases of corruption involving the president and members of the government came to light. Callejas has later been brought to trial for corruption and misuse of public funds.

The 1993 election was won by Carlos Roberto Reina of the Liberal Party, Partido Liberal de Honduras (PLH), a recognized human rights lawyer to whom high hopes were attached. Reina’s government made great efforts to correct its predecessors’ policies, but the counter-forces were strong. Inflation, unemployment, the poverty gap and crime continued to rise. The new government also did not have sufficient political strength for its fight against corruption. The judicial system also proved too corrupt and under pressure from the military and death squads. But it was better to track. The army’s immunity to scrutiny was gradually diminished, and several officers were eventually convicted of civilian abuse, human rights violations, and other conditions in the 1980s.

The Liberal Party PLH triumphed again in the fall of 1997, and Carlos Flores Facussé was able to form a new government – with the restructuring of the defense as one of its main causes. After more than 15 years of civilian government, the military continued to be a significant political power factor. The army’s own intelligence apparatus, FUSEP, which was largely targeted at the civilian population, was intact. In 1998, however, the police department was transferred from the military to the government, and two years later the country’s armed forces were also formally subject to civilian control.

Violation of human rights was still a serious problem, according to several reports. In 2000, it was discovered that the death squads had killed more than a thousand street children, and were also behind the attacks on the country’s indigenous population, partly with the support of the police. The UN made a strong appeal to the government to intervene.

In late winter 1999, tensions between Nicaragua and Honduras increased after Honduras awarded Colombia the right to a sea area that Nicaragua also claims. Troop reinforcements were sent to the border, and in February 2000 there was an exchange of gunfire between patrol boats from the two countries. Following meetings in Washington with mediation led by the Organization of American States (OAS), an agreement to avoid armed conflict was signed; the dispute was finally resolved in 2007. A similar, protracted border dispute with El Salvador found its solution in 2006.

In January 2002, the Conservative National Party’s Ricardo Maduro took office as new president, after winning the election in the fall. Maduro’s foremost program item was zero tolerance for the criminal gangs, the so-called maras. There were sharp reactions both at home and internationally when he declared that military forces should be deployed; by the way, his only son had to face life during a kidnapping four years earlier. Under the Maduro government, Honduras joined the US war in Iraq, as the first country in Central America, and restored, as one of the very last countries, diplomatic relations with Cuba.

Social and economic challenges

In October 1998, Honduras was hit by Hurricane Mitch, with a force never before experienced. Around 5,000 people lost their lives, 70 percent of the crops were lost, and the material destruction was enormous. Two years later, the grain harvest failed due to drought, and a UN-led aid program was set up to prevent hunger in the population. The natural disasters around the turn of the century were estimated to have set the trend back 20 years.

In the latter half of the 1990s, Honduras sailed as one of Central America’s foremost industrial countries. A number of North American and Asian companies have established operations in the San Pedro Sula area, having been lured to the country with tax exemptions and cheap labor. Large sums are invested in a modern road network that also links Honduras to ports on the Pacific side of El Salvador.

Throughout the first decade of the 2000s, Honduras figured among the Latin American countries with the strongest economic growth. But despite a noticeable improvement in several areas, the country was still among Central America’s least developed, with a rising poverty gap and a significant corruption problem. Up to 40% of the state budget helped to pay off debt. And the official unemployment rate was 30%, 70% of the population lived below the poverty line, while HIV/AIDS was a growing health problem. Measures to address the major crime and violence problems have also been high on the agenda of the recent presidential elections; in 2006, Honduras experienced its first political killing since the 1980s, when the ruling party’s group leader in the National Assembly was shot in his own home.

Military Bargain

In 2005, Honduras ratified a free trade agreement between Central American countries and the United States, something both the rival center/right parties, PLH and PNH, considered as a key strategy for economic progress. However, under PLH’s Manuel Zelaya, who won a pinch victory in the 2005 presidential election, Honduras joined in 2008 the competing Latin American trade cooperation ALBA, which was led by Venezuela’s US-hostile President Hugo Chavez. This left turn in Honduran foreign policy was justified by a lack of international support in the work to overcome the country’s poverty problem.

Manuel Zelaya took office as president in 2006, elected on a program to fight poverty and law and order as the main issue. At the time of the new presidential election in the summer of 2009, Zelaya wanted to organize a referendum that could, among other things, allow him to run for a new term. Like many other countries in the region, Honduras also has constitutional provisions that prevent reelection after a presidential term. When Zelaya wanted to conduct the referendum, he was deposed in a military coup initiated by the Supreme Court, and Roberto Micheletti was inducted as president.

The coup was condemned by most international leaders, including US President Barack Obama. After a turbulent period, presidential elections were held in November 2009, when the Conservative candidate Porfirio Lobo Sosa of the old power elite was declared the winner. Lobo’s foremost promise was to start “the great national dialogue” to unite the nation after the military coup. However, both the electoral process and the outcome were disputed, also in the rest of Latin America, where a number of heads of state believed the election laundered the coup makers and increased the danger of new military coups in the region. Unlike the United States, neither the United Nations nor the Organization of American States (OAS) recognized the election.

The 2013 presidential election, approved by election observers, was won by conservative Juan Orlando Hernández. With anti-crime and anti-corruption laws, which now permeate the Honduran community, Hernández has signed a transparency agreement with Transparency International, among others.